Tutorial 6. Logical conditionals

Exercise sheet

Equivalences

For each of the following pairs of formulas, show that they are equivalent in the sense that they have the same truth-value under each valuation.

a)

$A\to B$ and $\neg A\lor B$

b)

$A\to B$ and $\neg(A\land\neg B)$

c)

$A$ and $\neg A\to A$ ( Clavius ’s law)

d)

$A\to B$ and $\neg B\to \neg A$ (the law of contraposition)

e)

$A\to (B\to C)$ and $(A\land B)\to C$

Solution

You can solve these in various ways. Here I provide some different styles of solutions.

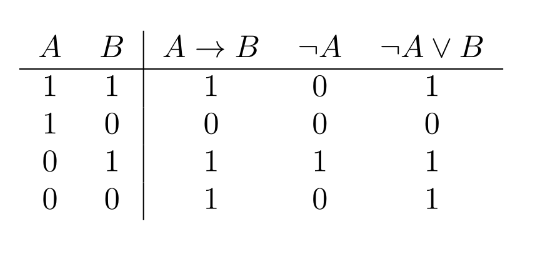

a)

We do this with a truth-table, which goes through all possible values:

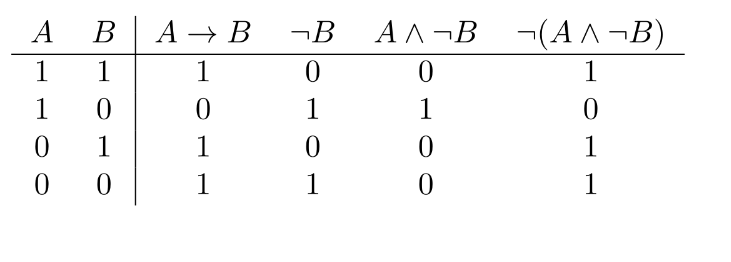

b)

Also here, truth-tables is a good method:

c)

Here we can give a rather simple argument:

$\nu(A)$ is either 0 or 1. If $\nu(A)=0$, then $\nu(\neg A)=1$. But then $v(\neg A\to A)=1\Rightarrow 0=0$. If, instead, $\nu(A)=1$, then $\nu(\neg A)=0$ and so $\nu(\neg A\to A)=0\Rightarrow \nu(A)=1$.

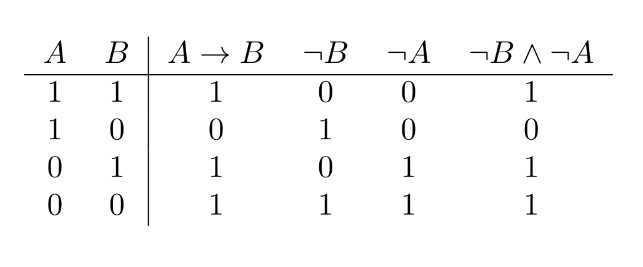

d)

We do a truth-table:

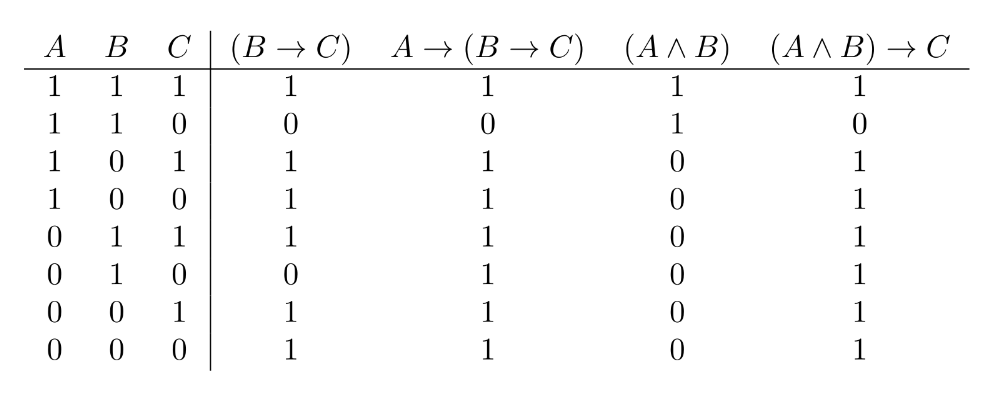

e)

Here we can give a more sophisticated argument:

The only way in which we can have $\nu(A\to(B\to C))=0$ is if $\nu(A)=1$, $\nu(B\to C)=0$. The latter can only be if $\nu(B)=1$ and $\nu(C)=0$. But then, $\nu(A\land B)=1$ and $\nu(C)=0$ and so $\nu((A\land B)\to C)=\nu(A\land B)\Rightarrow \nu(C)=1\Rightarrow 0=0$.

Similarly, the only way in which $\nu((A\land B)\to C)=0$ is if $\nu(A\land B)=1$ and $\nu(C)=0$. But then $\nu(A)=1$ and $\nu(B)=1$, since $\nu(A\land B)=\nu(A)\times\nu(B)=1$. But then $\nu(B\to C)=0$ since $\nu(B\to C)=\nu(B)\Rightarrow\nu(C)=1\Rightarrow 0$ and so $\nu(A\to (B\to C)=\nu(A)\Rightarrow \nu(B\to C)=1\Rightarrow 0=0$.

So the two formulas are false in the exact same cases, which means in all other cases they must both be true.

Alternatively, you can do an 8-row truth-table:

Boolean laws

Formulate the equivalences from Exercise 1 as Boolean laws. For example, a) becomes $$x\Rightarrow y=-x+y.$$

Solution

a)

$$x\Rightarrow y=-x+y.$$

b)

$$x\Rightarrow y=-(x\times -y)$$

c)

$$x=-x\Rightarrow x$$

d)

$$x\Rightarrow y=-y\Rightarrow -x$$

e)

$$x\Rightarrow(y\Rightarrow z)=(x\times y)\Rightarrow z$$

Validities

Check the validity of the following inferences using a suitable method (DPLL, truth-tables, …).

a)

$\mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{CAR}\vDash (\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})\to \mathsf{CAR}$

b)

$\mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{CAR}, \mathsf{CAR}\to \mathsf{KEYS}\vDash \mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{KEYS}$

c)

$\mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{CAR},\mathsf{CAR}\vDash \mathsf{RAIN}$

d)

$\mathsf{SUN}\to \mathsf{BIKE},\neg\mathsf{SUN}\vDash \neg \mathsf{BIKE}$

Solution

There are many different options, we sample to show the variety:

a)

$\mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{CAR}\vDash (\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})\to \mathsf{CAR}$

Here we use a semantic argument: Suppose that $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\to\mathsf{CAR})=1$. The only way in which $\nu((\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})\to \mathsf{CAR})=0$ is if $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})=1$ and $\nu(\mathsf{CAR})=0$. But if $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})=1$, then $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN})=1$. Since $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\to\mathsf{CAR})=1$, this means that $\mathsf{CAR}=1$ (since otherwise $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\to\mathsf{CAR})=0$). So, for $\nu((\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})\to \mathsf{CAR})=0$ we have to both have $\nu(\mathsf{CAR})=1$ and $\nu(\mathsf{CAR})=0$, which is impossible. Consequently, $\nu((\mathsf{RAIN}\land \mathsf{WARM})\to \mathsf{CAR})=0$ is impossible if $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN}\to\mathsf{CAR})=1$.

This means the inference is valid.

b)

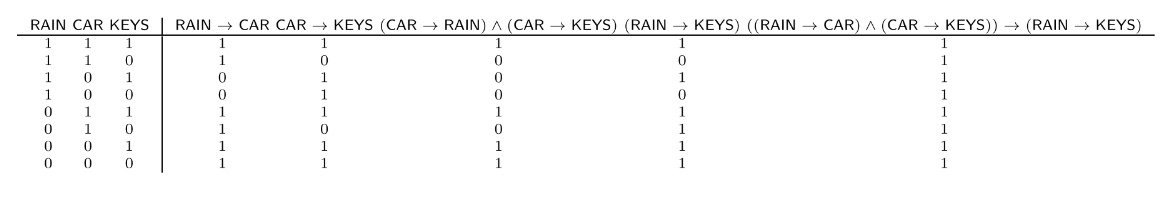

Let’s do a big truthtable:

Since the relevant conditional is a logical truth, the inference is valid.

c)

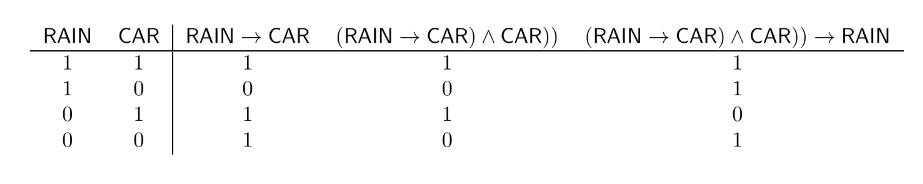

This inference is _in_valid. We can see this, for example, using a truth-table:

As you can see, if you set $\nu(\mathsf{CAR})=1$ and $\nu(\mathsf{RAIN})=0$, we have both premises true, but the conclusion false.

d)

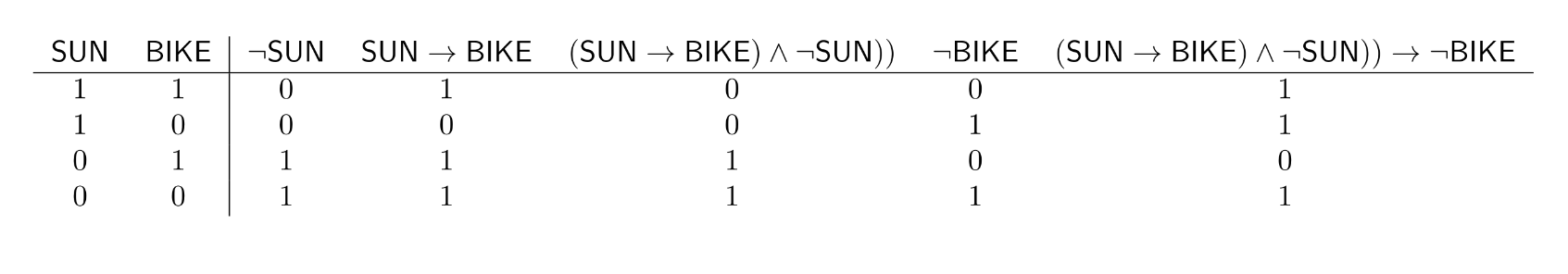

Also here a truth-table gives a quick answer:

We see that if we set $\mathsf{BIKE}=1$ and $\mathsf{SUN}=0$, the premises are true and the conclusion false.

Horn clauses

Remember that a literal is a propositional variable or its negation. A Horn clause is a disjunction of literals, where at most one literal is positive meaning it doesn’t contain a negation. This means that a Horn clause has the form: $$\neg p_1\lor \neg p_2\lor \dots\lor q,$$ where $p_1,p_2,\dots,q$ are propositional variables.

a)

Provide an argument that every Horn clause is equivalent to (=always has the same truth-value as) a conditional of the form: $$p_1\land p_2\land\dots \to q.$$

Hint: There are different routes to this result, but you’ll need to use Boolean laws/corresponding logical equivalences. Here are some candidates to use in your argument:

$$x\Rightarrow y = -x+y$$

$$x\Rightarrow (y\Rightarrow z)=(x\times y)\Rightarrow z$$

$$-x+-y+\dots=-(x\times y\times \dots)$$

b)

Can every formula equivalently be written as a Horn clause?

Solution

a)

Pick an arbitrary Horn clause.

$$\neg p_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg p_n\lor q$$

This is the boolean algebra truth-conditions:

$$- p_1 + \ldots + - p_n+q$$

By DeMorgan principles this is equivalent to:

$$-(p_1 \times \ldots \times p_n)+q$$

By conditional laws (from exercise 2) we get:

$$(p_1 \times \ldots \times p_n)\Rightarrow q$$

Which is the truth-condition of the following formula:

$$(p_1 \land \ldots \land p_n)\rightarrow q$$

b)

No. Example: $p\land q$ does not have an equivalent Horn form.

Consider an arbitrary Horn clause $\neg r_1\lor\neg r_2\lor\ldots\lor s$. Call it $A$. Since $A$ has at most one positive part $s$ by definition, the following thing must happen in all valuations: $\nu(A)=1$ if and only if $\nu(r_i)=0$ for one of its negative parts or $\nu(s)=1$ for its positive part. This gives us a general idea of the format of truth-conditions for any Horn clause.

Now, pick a Horn clause $B$ that involves the literals $p$ and $q$ as parts. Could this be equivalent to the conjunction $p\land q$? We will show that it cannot be. There are only three possibilities for the shape of this Horn clause:

- $p$ is a positive part of $B$

- $q$ is a positive part of $B$

- neither $p$ nor $q$ is positive in $B$

In situation 1. the literal $q$ must be a negative part of $B$, so whenever $\nu(B)=1$, then $\nu(q)=0$. Obviously that means $B$ is not equivalent to $p\land q$. In situation 2. the literal $p$ must be negative in $B$, so whenever $\nu(B)=1$, then $\nu(p)=0$. Obviously that means $B$ is not equivalent to $p\land q$. In situation 3. both $p$ and $q$ would be negative parts of $B$ so we get an even worse result.

Resolution

A disjunction of literals, we call a (disjunctive) clause.

The resolution rule says that if you have two clauses ($l_i,k_j$ are literals)

$$l_1\lor l_2\lor \dots\lor p \qquad \qquad \neg p\lor k_1\lor k_2\lor\dots$$

you can infer:

$$l_1\lor l_2\lor \dots k_1\lor k_2\lor\dots$$

So, for example, from

$$\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\neg\mathsf{SUN}\lor\mathsf{BIKE}\qquad \neg\mathsf{BIKE}\lor\mathsf{HELMET}$$ you can infer $$\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\neg\mathsf{SUN}\lor\mathsf{HELMET}$$

a)

Show that the example inference is valid using a suitable method (truth-tables, DPLL, …).

b)

Use the resolution rule to show that the following inference is valid:

$$\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\mathsf{BIKE},\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\vDash \mathsf{BIKE}$$

Which rule of the DPLL algorithm does this correspond to?

c)

We can use the resolution to define a general inference method:

-

To test whether $P_1,P_2,\dots\vDash C$ we bring $P_1\land P_2\land \dots\land \neg C$ into CNF (see Chapter 5.3 ).

-

We then recursively apply the resolution rule to all possible combinations of clauses (and the results of those applications, the results of the results, …).

-

Outcome:

-

If any application of the resolution rule results in an empty clause $\Set{}$, the inference is valid.

-

If we arrive at a point where no more applications are possible and no empty clause has been derived, the inference is invalid.

-

Use this method to show that the following inference is valid:

$$\mathsf{RAIN}\vDash \mathsf{RAIN}\land (\mathsf{RAIN}\lor \mathsf{SUN})$$

d)

The result of applying the resolution rule to two Horn clauses always results in a Horn clause. Why?

e)

Use the resolution rule (together with Exercise 1 a)) to show that the following inference is valid:

$$\mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{CAR}, \mathsf{CAR}\to \mathsf{KEYS}\vDash \mathsf{RAIN}\to \mathsf{KEYS}$$

f)

The inference pattern $$A\to B,B\to C\vDash A\to C$$ is known as “transitivity” for the logical conditional.

Use the reasoning from e) together with Exercise 4 a) to show that the application of the resolution rule to Horn clauses is essentially just an application of the transitivity principle.

What does this have to do with the forward and backward chaining methods?

Solution

a)

We want to show that this is valid:

$$l_1\lor l_2\lor\ldots\lor p ,; \neg p\lor k_1\lor k_2\lor\ldots \vDash l_1\lor l_2\lor\ldots\lor k_1\lor k_2\lor\ldots $$

To do this, we will think about the premises combined with the negation of the conclusion. This is what the negation of the conclusion looks like.

$\neg(l_1\lor l_2\lor\ldots\lor k_1\lor k_2\lor\ldots)$

Convert the negated conclusion into CNF.

$\neg l_1\land\neg l_2\land\ldots\land\neg k_1\land\neg k_2\land\ldots$

Together with the premises, this gives us a set of conditions.

$\Set{ \Set{l_1, l_2,\ldots p },\Set{\neg p, k_1, k_2,\ldots },\Set{\neg l_1 }, \Set{\neg l_2 }, \ldots, \Set{\neg k_1 }, \Set{\neg k_2 }, \ldots, $

By unit propogation on $\neg l_1$ we get:

$\Set{ \Set{ l_2,\ldots p },\Set{ \neg p, k_1, k_2,\ldots },\Set{ \neg l_2 }, \ldots, \Set{ \neg k_1 }, \Set{ \neg k_2 }, \ldots, }$

Continue unit propogation with each $\neg l_i$ to get:

$\Set{ \Set{ p }, \Set{ \neg p, k_1, k_2,\ldots }, \Set{ \neg k_1 }, \Set{ \neg k_2 }, \ldots, }$

By unit propogation on $\neg k_1$ we get:

$\Set{ \Set{ p }, \Set{ \neg p, k_2,\ldots }, \Set{ \neg k_2 }, \ldots, }$

Continue unit propogation with each $\neg k_j$ to get:

$\Set{ \Set{ p }, \Set{ \neg p } }$

A final step of unit propogation on $p$ shows us that the set is unsatisfiable.

$\Set{ \Set{ } }$

This means that it is impossible to make the premises and negation of the conclusion true. Which means that the inference is valid.

b)

This inference, called the Disjunctive Syllogism (DS), is just an application of the Resolution Rule. We just showed in part (a) that the Resolution Rule always leads to valid reasoning. So this gives us a new way to see why DS is valid. The reasoning we use for resolution is just like the Splitting rule of the DPLL algorithm.

c)

We take the premises combined with the negation of the conclusion and convert into a single CNF formula:

$\mathsf{RAIN}\land(\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\neg\mathsf{RAIN})\land(\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\neg\mathsf{SUN})$

So we have this set of conditions.

$\Set{ \Set{ \mathsf{RAIN} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN},\neg\mathsf{RAIN} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN},\neg\mathsf{SUN} } }$

Equivalent to this set of conditions.

$\Set{ \Set{ \mathsf{RAIN} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN},\neg\mathsf{SUN} } }$

By applying the Resolution Rule on the first two clauses we get:

$\Set{ \Set{ }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN},\neg\mathsf{SUN} } }$

Since there is an empty set, this shows that the inference is valid.

d)

The only time we can apply the Resolution Rule to two Horn clauses is when the same literal occurs as a positive part in one Horn clause and a negative part in the other Horn clause. Like the literal $q$ in these two formulas:

$$\neg p_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg p_n\lor q$$

$$\neg q\lor\neg r_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg r_m\lor s$$

When we apply the Resolution Rule we get this:

$$\neg p_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg p_n\lor\neg r_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg r_m\lor s$$

Since the original two formulas had only one positive part, and the positive $q$ was eliminated by Resolution, this means that the final formula also has only one positive part. Which means that it still qualifies as a Horn clause.

e) We take the premises combined with the negation of the conclusion and convert into a single CNF formula:

$(\neg\mathsf{RAIN}\lor\mathsf{CAR})\land(\neg\mathsf{CAR}\lor\mathsf{KEYS})\land\mathsf{RAIN}\land\neg\mathsf{KEYS}$

So we have this set of conditions.

$\Set{ \Set{ \neg\mathsf{RAIN},\mathsf{CAR} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{CAR},\mathsf{KEYS} }, \Set{ \mathsf{RAIN} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{KEYS} } }$

Apply the Resolution Rule on $\mathsf{RAIN}$.

$\Set{ \Set{ \mathsf{CAR} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{CAR},\mathsf{KEYS} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{KEYS} } }$

Apply the Resolution Rule on $\mathsf{CAR}$.

$\Set{ \Set{ \mathsf{KEYS} }, \Set{ \neg\mathsf{KEYS} } }$

Apply the Resolution Rule on $\mathsf{KEYS}$.

$\Set{ \Set{ } }$

Since there is an empty set, this shows that the inference is valid.

f)

If we have two simply Horn clauses that are eligible for Resolution, they look like this.

$$\neg p_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg p_n\lor q$$

$$\neg q\lor\neg r_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg r_m\lor s$$

These are equivalent to:

$$(p_1\land\ldots\land p_n)\rightarrow q$$

$$q\rightarrow((r_1\ldots\land r_m)\rightarrow s)$$

Generalizing from exercise (5e) we can see how these premises validly imply the formula below, by using the Resolution rule.

$$(p_1\land\ldots\land p_n)\rightarrow((r_1\ldots\land r_m)\rightarrow s)$$

Notice this is just an instance of Transitivity, but the result that it gives us is equivalent to the formula we reached in exericse (5d).

$$\neg p_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg p_n\lor\neg r_1\lor\ldots\lor\neg r_m\lor s$$

Discussion

Remember the Wason selection task from the teaser lecture (if you’re not a first-year AI student or missed the intro day lecture, check out the description on Wikipedia).

Some researchers have argued that the experiment shows that people don’t reason with the material/logical conditional in this case. Do you agree? Why?