Tutorial 2. Formal languages

Exercise sheet

Ambiguity

Which of the following statements in natural language are ambiguous? If you find an ambiguous statement, paraphrase the different readings to bring out the ambiguity. Try to find an inference, whose validity depends on the ambiguity, in the sense that it’s valid under one reading and invalid under the other.

-

I see his goose.

-

I see her duck.

-

He thanked her children, Alan and Ada.

-

They greeted their parents, Bob, and Betty.

-

I see a man with my binoculars.

-

There’s the woman with my telescope.

-

A friendly dog walker.

-

I’m happy I’m here, and so is she.

-

The priest married my uncle.

-

They fed her dog food.

Solution

-

This statement is (relatively) unambiguous.

-

There are at least two ways of reading this:

-

I see her perform the action of ducking (lowering the head or body quickly).

-

I see an animal of the species duck , which belongs to her.

On the first reading, you might for example infer (deductively) that she is now in a crouching position or (inductively) that she tried to avoid getting hit by something. On the second reading, you could infer (deductively) that she owns an animal. Neither inference is valid on the other reading.

-

-

Many people consider this ambiguous between:

-

He thanked her two children, called “Alan” and “Ada”.

-

He thanked her children, whoever they are, and two people called “Alan” and “Ada”.

On the first reading, you can infer that Alan is her child, while you cannot n the second reading.

-

-

This statement instead uses the serial comma to avoid the previous ambiguity.

-

This statement is ambiguous between:

-

I see a man who has my binoculars.

-

I see a man through my binoculars.

On the first reading, you can infer that the speaker does not currently have their binoculars in their possession, while on the second reading you can.

-

-

This statement is (relatively) unambiguous.

-

This phrase has the following two readings:

-

Someone who walks dogs and is friendly.

-

Someone who walks (only?) friendly dogs.

On the first reading, you can infer that the person is friendly, on the second you can’t.

-

-

There are two readings:

-

I am happy that I am here and she is happy that I’m here.

-

I am happy that I’m here and she is also here.

On the second reading you can, for example, infer that she is here, while on the second one you can’t.

-

-

This statement is ambiguous between:

-

The priest officiated my uncle’s wedding.

-

The priest got married to my uncle.

On the second reading, you can infer that the priest is now the speakers uncle in law, while on the first one you can’t.

-

-

Also this statement is ambiguous:

-

They fed her food for dogs

-

They fed food to her dog.

On the second reading, you can infer that she owns a dog, while on the first one you can’t.

Over-expressiveness

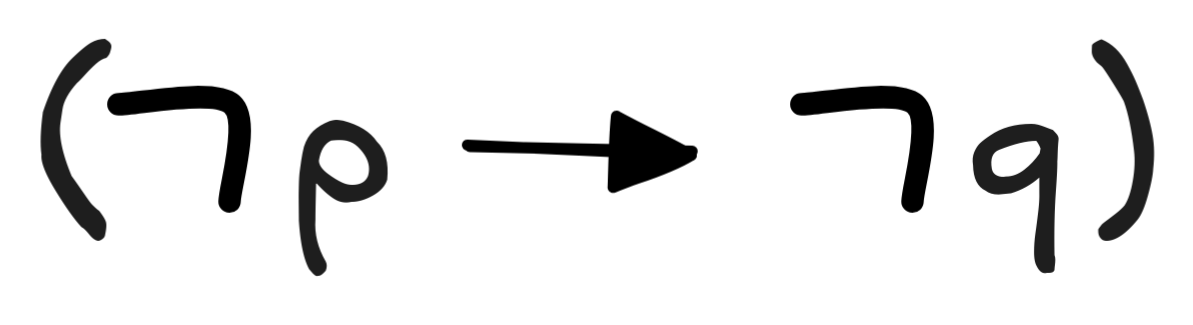

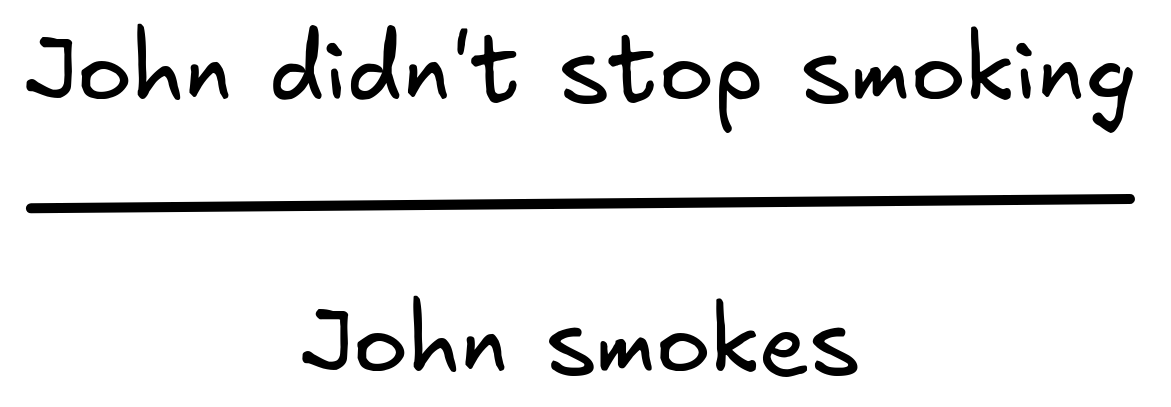

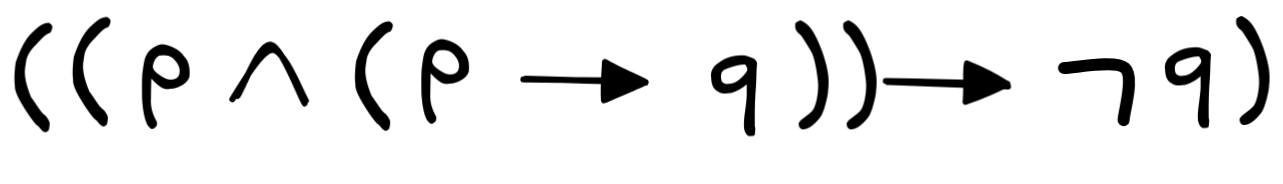

Consider the following inference:

The inference is deductively invalid. Show this by providing a scenario in which the premise is true and the conclusion isn’t. Explain how the over-expressiveness of natural language is responsible for the inference seeming to be valid.

Solution

We don’t know whether John smokes or not, but we can consider a situation, where he never smoked. In such a situation, he never stopped smoking, so the premise is true. But he’s not a smoker, so the conclusion isn’t true. This makes the inference invalid.

In natural language, we often convey meaning that goes beyond the literal meaning of statements, for example by means of implicature . In this case, we’re dealing with a seeming presupposition , where the first statement seems to have the implicit presupposition that John did smoke. This might make the inference seem valid, even though it isn’t.

Sets

Describe the following sets using set notation:

-

the set containing no object whatsoever—the so-called empty set

-

the set containing IA , Utrecht University, and the set containing IA and nothing else.

-

the set of all even numbers between 1 and 10

-

the set of all even numbers

-

the set of all non-empty sets that contain only the numbers 1, 2, and 3

Solution

-

{ }, with nothing written between the curly brackets. There is also the set-theoretic symbol ∅.

-

{ IA , UU, {IA } }

-

{ 2, 4, 6, 8 } or { n : n is an even number between 1 and 10}

-

{ n : n is an even natural number }

-

{ {1}, {2}, {3}, {1,2}, {1,3}, {2,3}, {1,2,3} } or:

{ x : x is a non-empty set with only member from {1, 2, 3} }

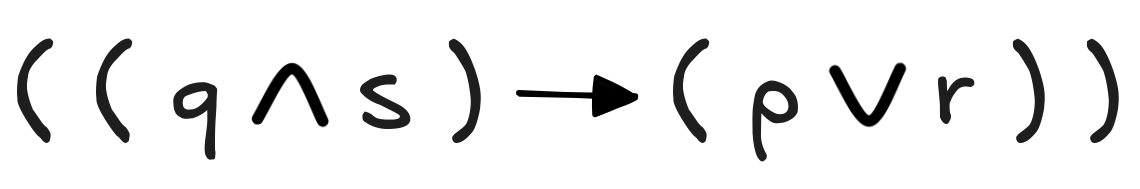

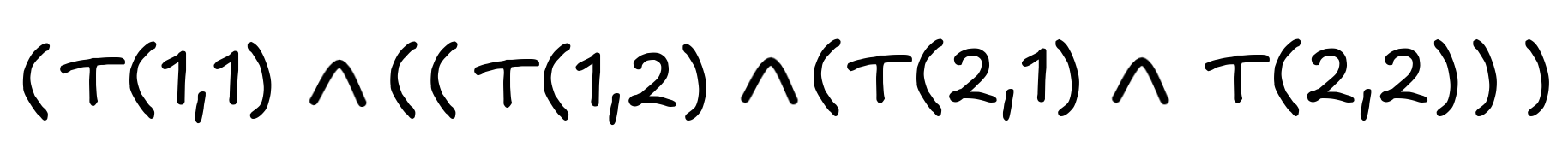

Parsing

Parse the following formulas according to the grammar of propositional logic. You can either do this by giving the rewrite sequence or the parsing tree.

Solutions

-

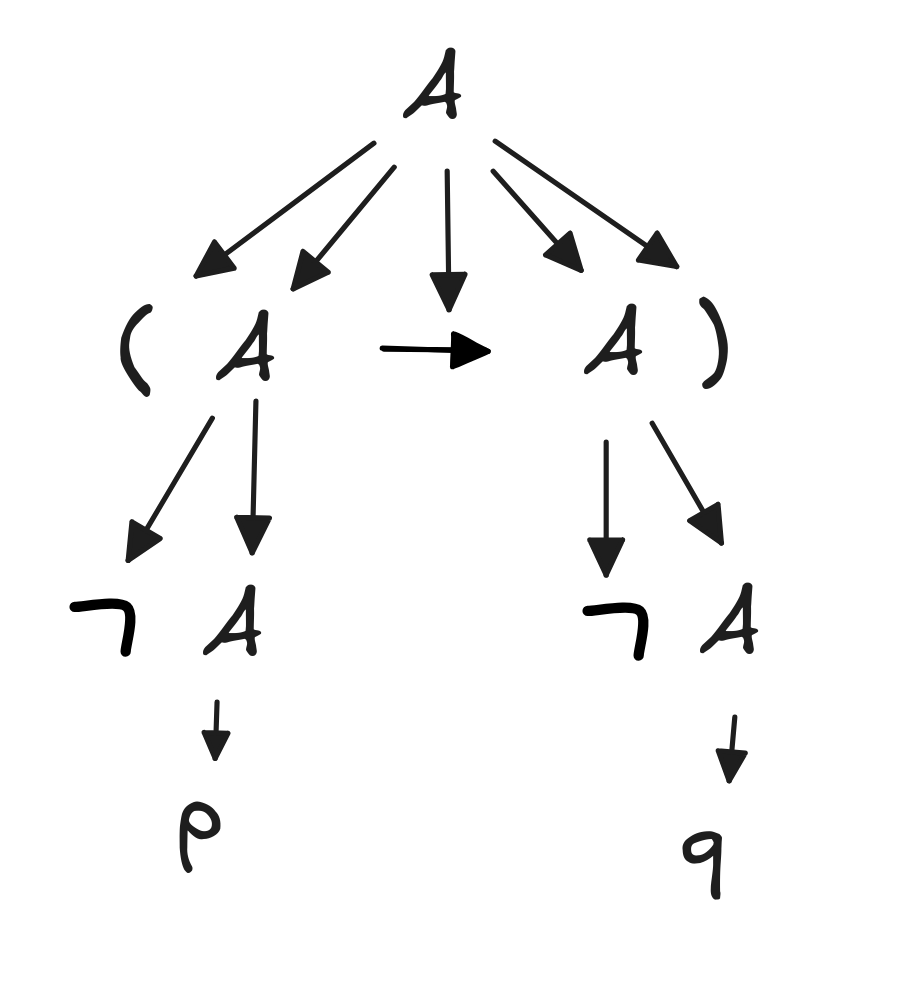

Here’s the parse tree:

-

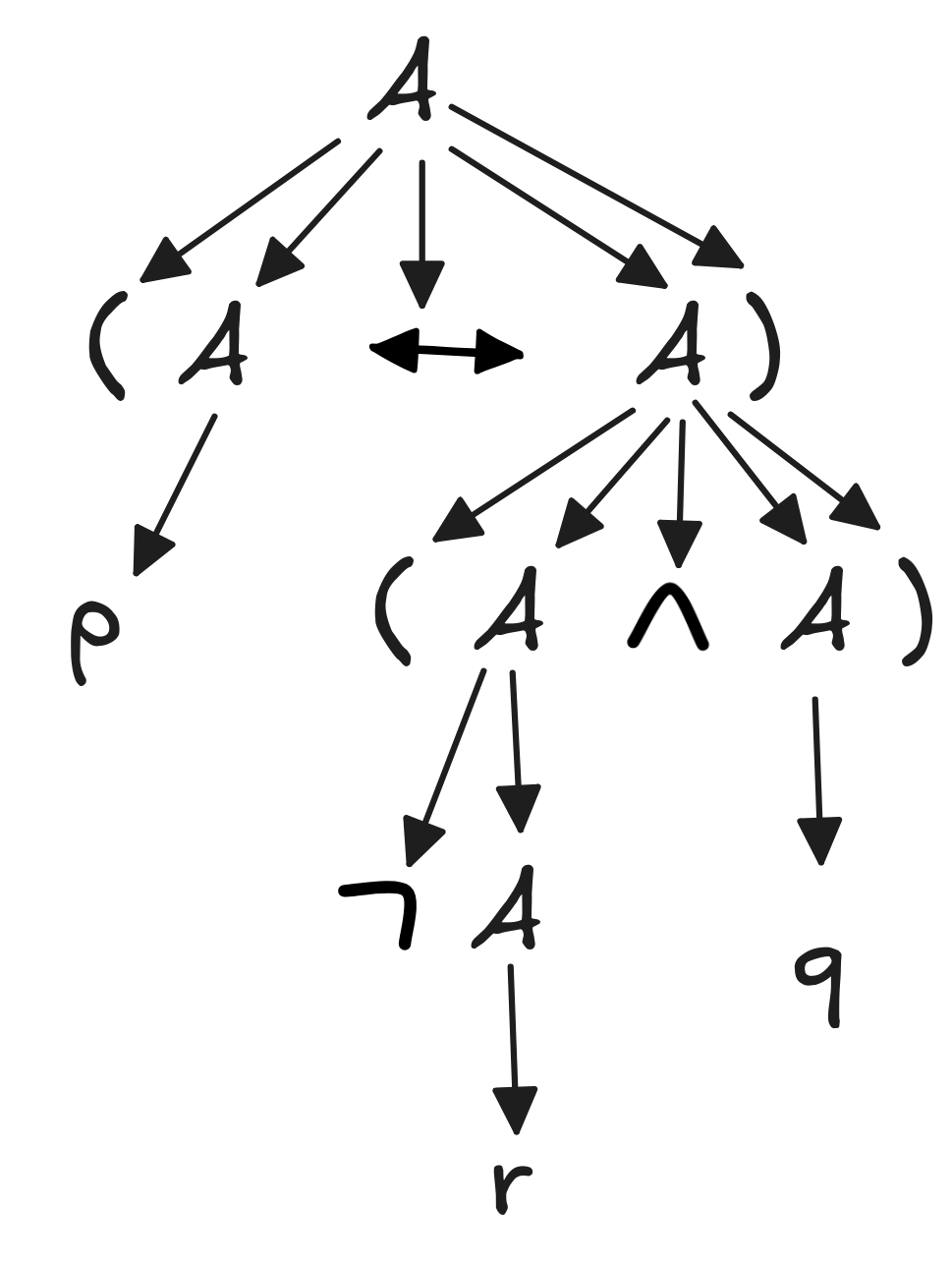

Here’s the parse tree:

-

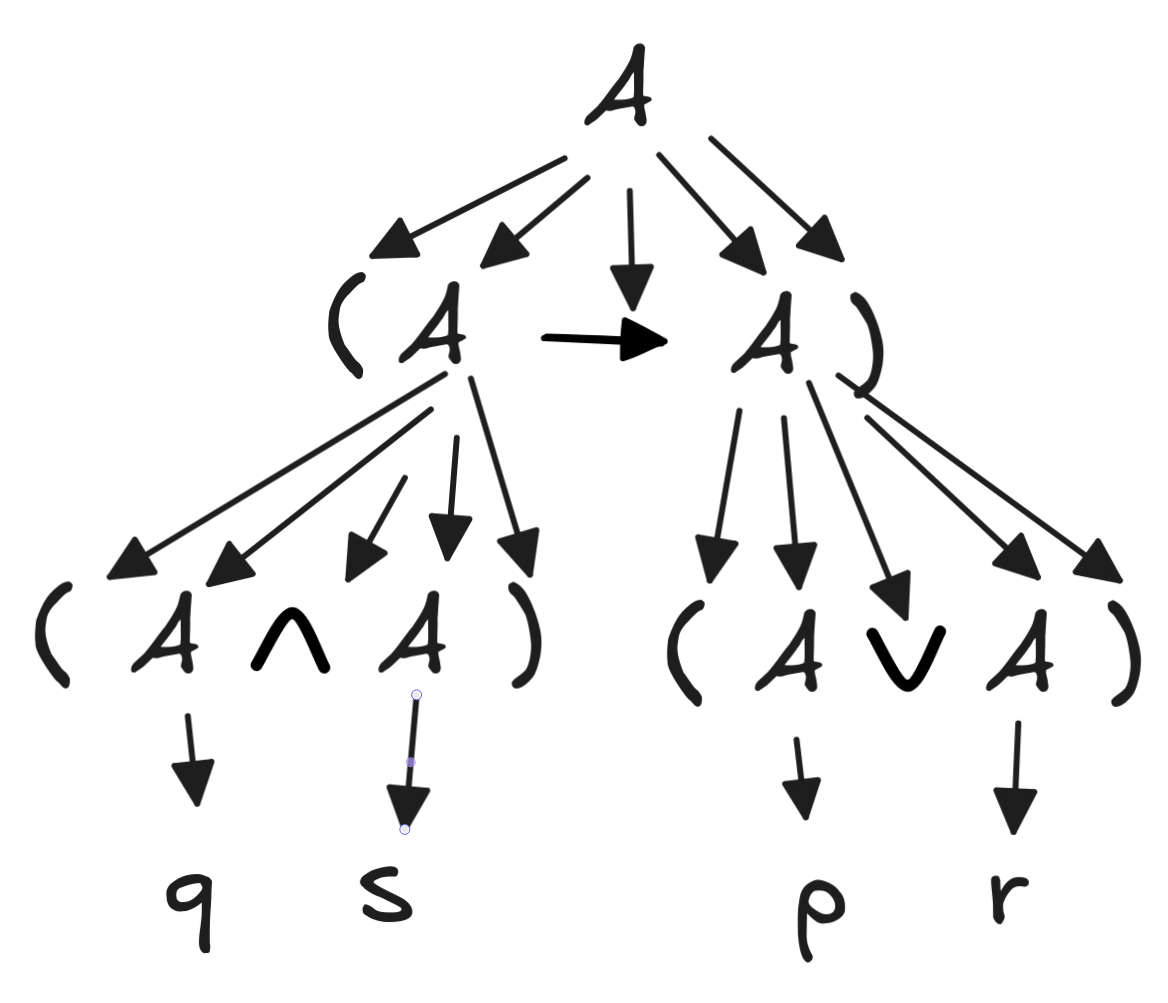

Here’s the parse tree:

-

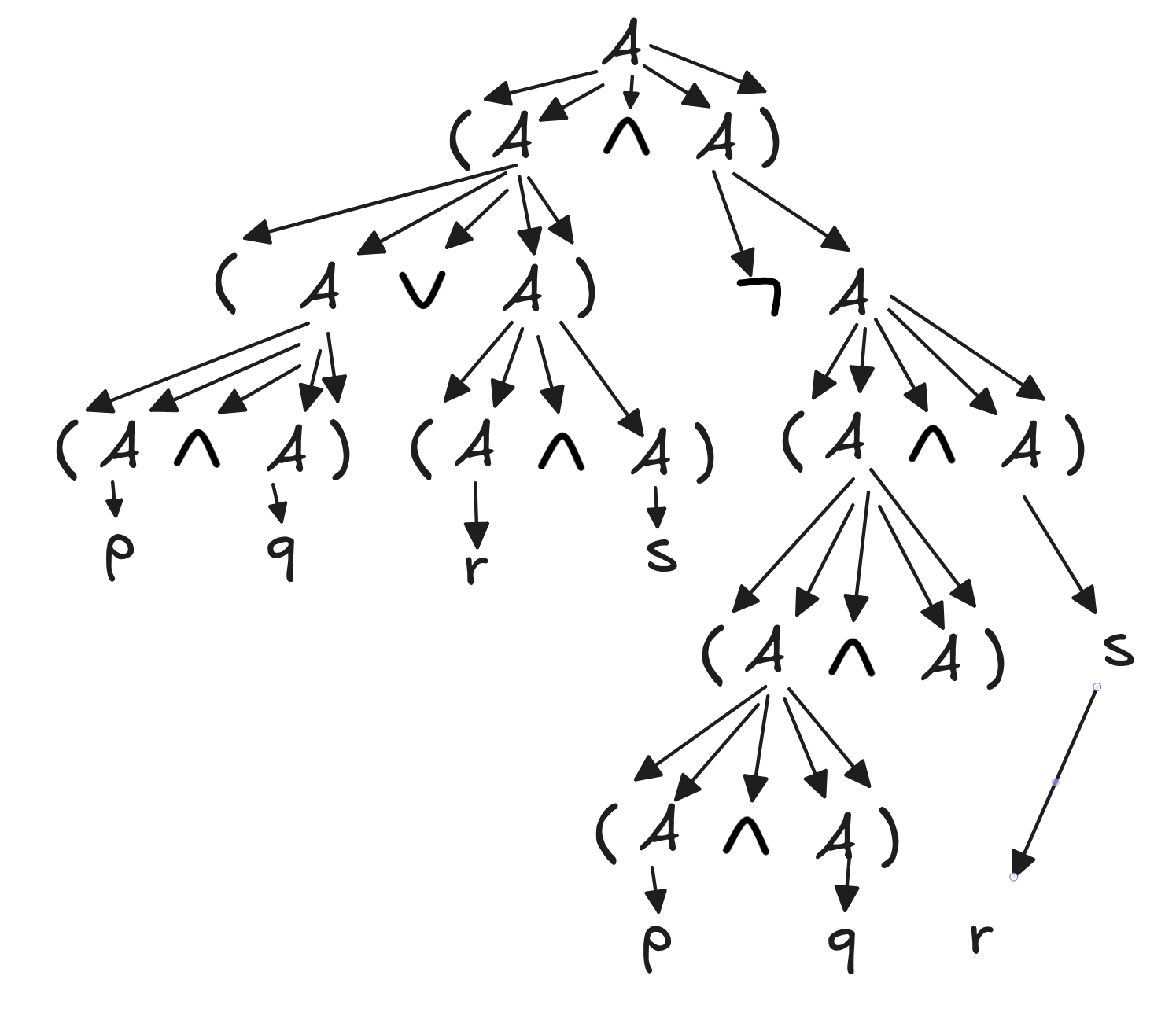

Here’s the parse tree:

Polish notation

In the lesson on formal languages, we explained the need for parentheses in order to avoid ambiguity in the language for propositional logic.

But it turns out that there’s another way, which is known as Polish notation , in honor of the Polish logician Jan Łukasiewicz , who pioneered it.

We’ll look at a simple proposition language in Polish notation, with the following alphabet:

The letters

p,q,r

are propositional variables,

and

N

stands for negation

,

K

for conjunction

,

K

for conjunction

,

A

for disjunction

,

A

for disjunction

,

C

for the conditional

,

C

for the conditional

, and

B

for the bi-conditional

, and

B

for the bi-conditional

,

,

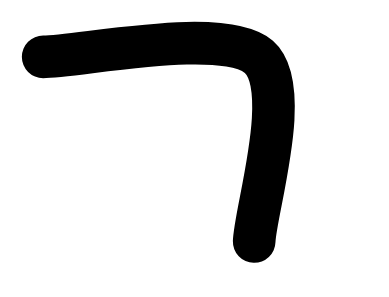

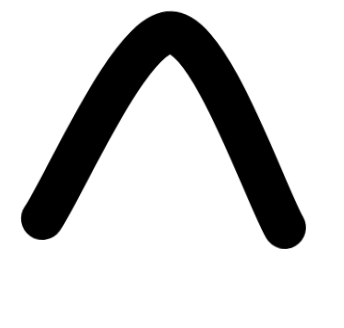

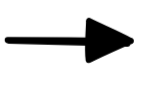

Polish notation is a prefix notation as compared to the usual infix

notation. That is, instead of writing

, for example, we write

CKpCpqNq

.

, for example, we write

CKpCpqNq

.

-

Determine the grammar of Polish notation both in terms of recursive clauses and as a BNF.

-

Determine the corresponding re-write rules and generate the parsing tree for CKpCpqNq .

-

Give an argument why pCpqNqCpr is not a formula in Polish notation.

-

Go back to the example from the textbook which illustrated the need for parentheses when using infix notation and write the corresponding formulas in Polish notation. Explain with the example why we no longer need parentheses in Polish notation.

Solution

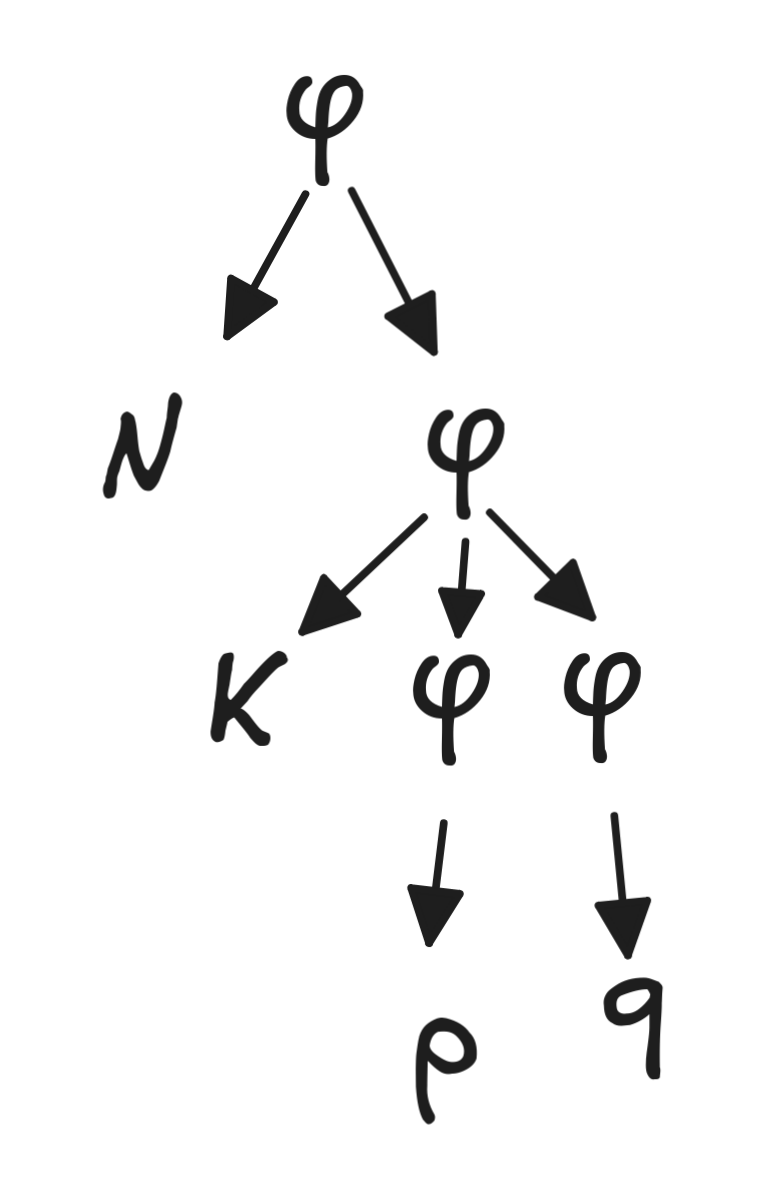

- I’m using ϕ as the variable in the form, rather than A as before to avoid confusion with the symbol for disjunction:

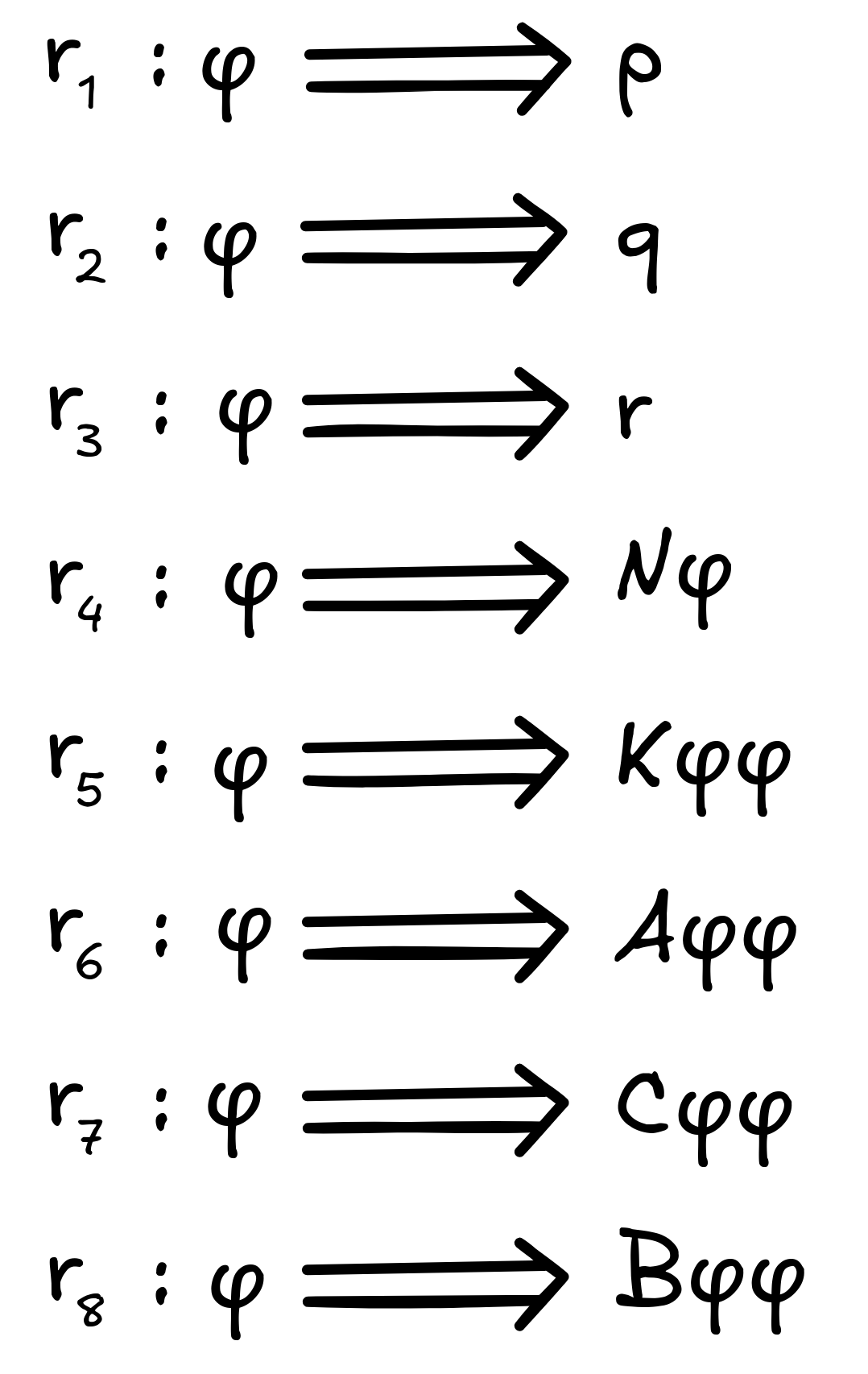

- Here are the rewrite rules:

And here’s the tree:

-

pCpqNqCpr can’t be a formula in Polish notation since there are only two options: either a formula starts with an operator from N,K,A,C,B or it is a propositional variable. But this formula starts with a propositional variable and then continues. There is no rule, which can generate such a formula, so it isn’t one.

-

The formula was

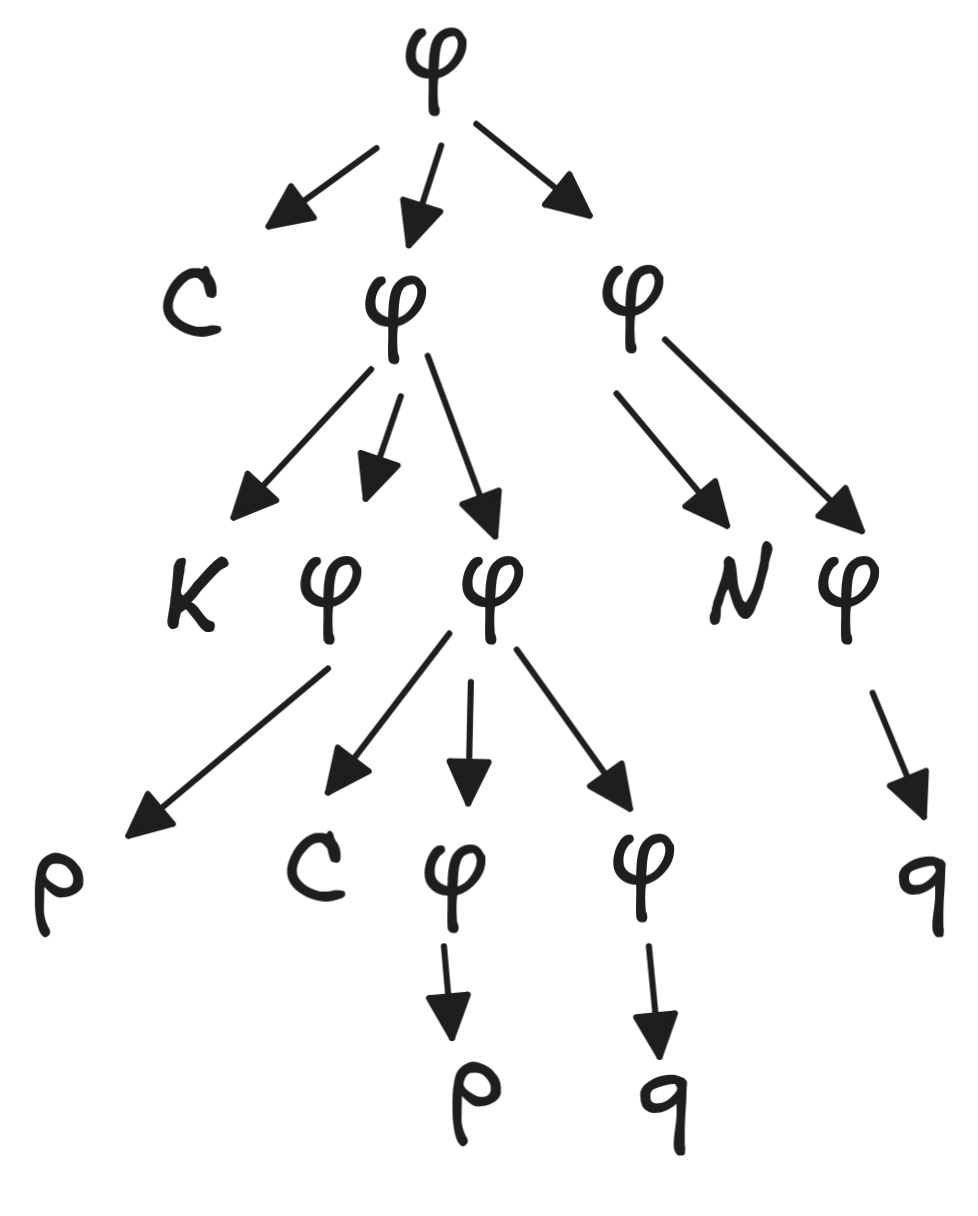

. If we write this in Polish notation, it becomes NKpq. But this formula now has a unique reading, given by the following parse tree:

. If we write this in Polish notation, it becomes NKpq. But this formula now has a unique reading, given by the following parse tree:

If we wanted to give it “the other” reading, we would need to write KNpq.

Knowledge representation

IA has taken up privateering. Now, he’s got a treasure of numerous Bitcoin, rare computer chips, and Alan Turing’s old KB.

IA hid the treasure on some remote disk-world and now he’s trying to write instructions on how to find the treasure. Since he’s an AI system, he does so using propositional logic.

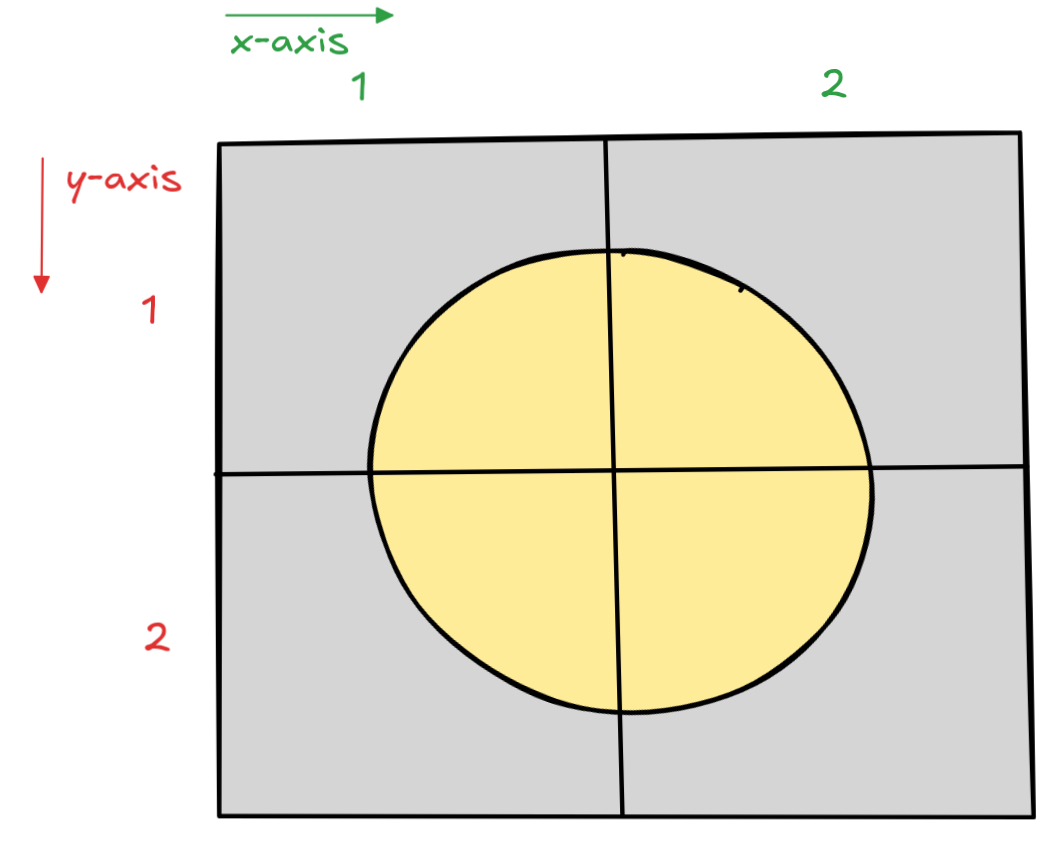

First, he divided the disk-world into 4 quadrants, indicating in the following coordinate system:

He then devised a formal language with propositional variables T(i,j) to say that the treasure is at coordinate (i,j) with the first component being the x -axis and the second the y -axis.

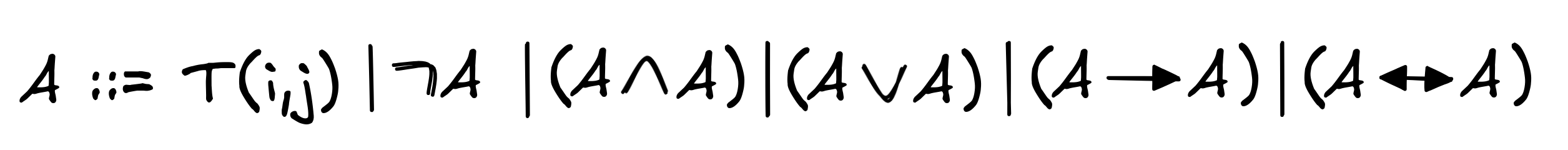

Correspondingly, the BNF of his language is:

Help IA to represent the following hints about the treasure’s location in the resulting language:

-

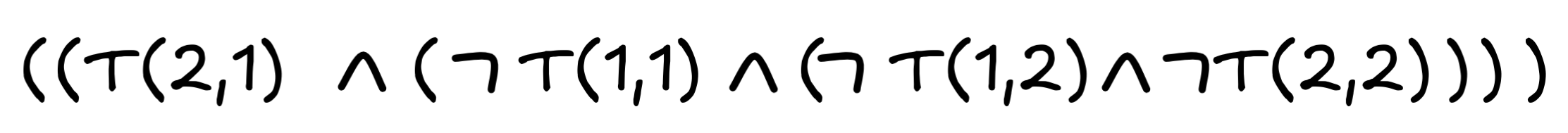

The treasure is in the upper right quadrant and in none of the other quadrants.

-

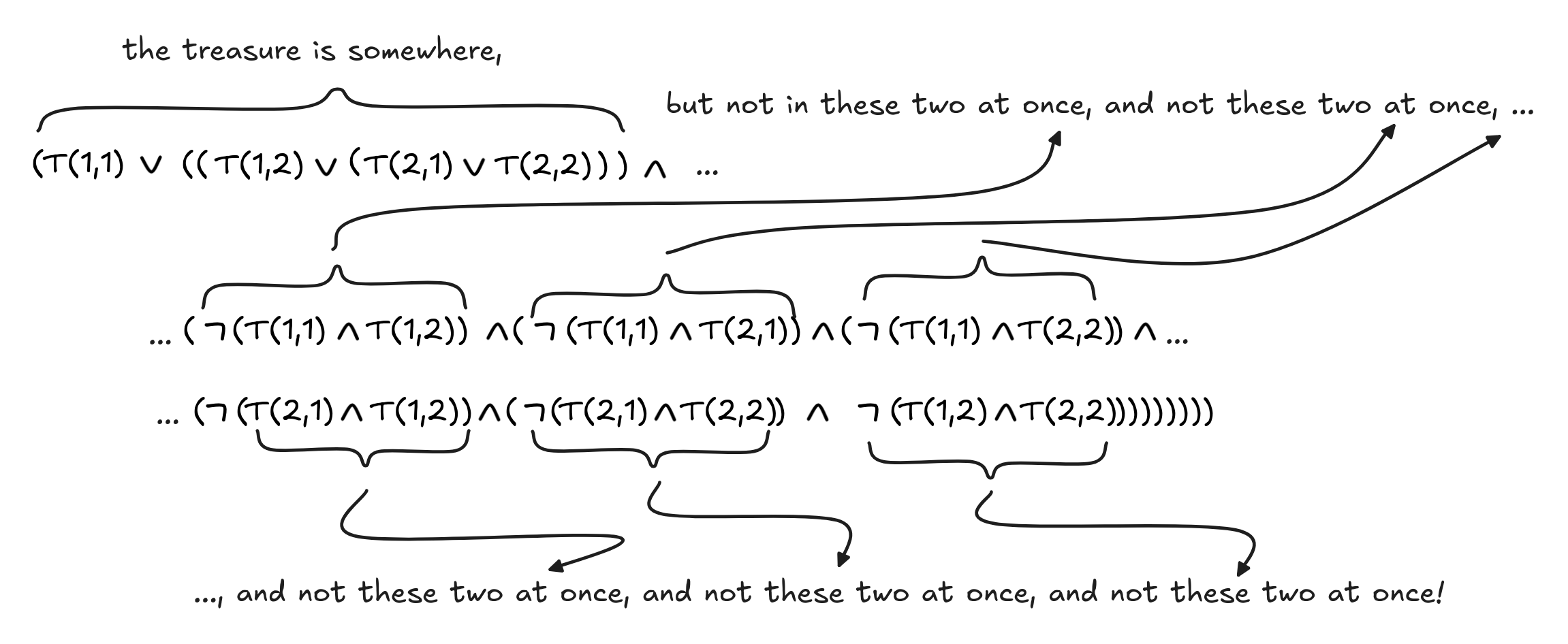

The treasure is in exactly one quadrant, that is, it is either in the upper left, upper right, lower left, or lower right quadrant, but not in any two quadrants at the same time.

-

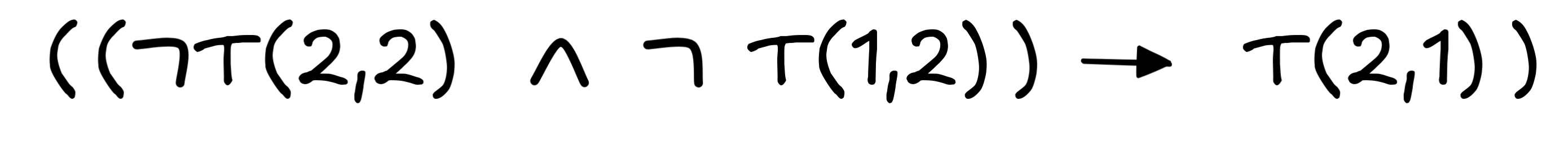

If the treasure is not in the lower right quadrant, then it’s in the upper left quadrant, but only if it’s not in the lower left quadrant.

-

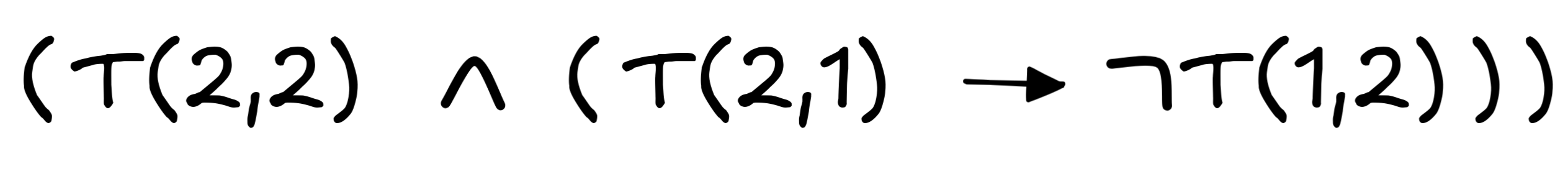

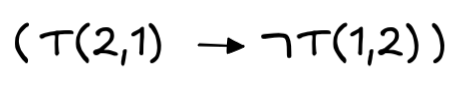

The treasure is only in the upper right quadrant, if it is not in the lower right quadrant.

-

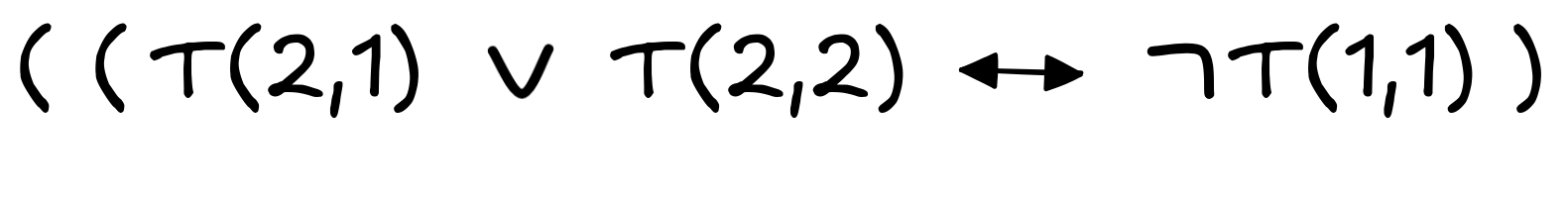

The treasure is in any of the right quadrants just in case it is not in the upper left quadrant.

-

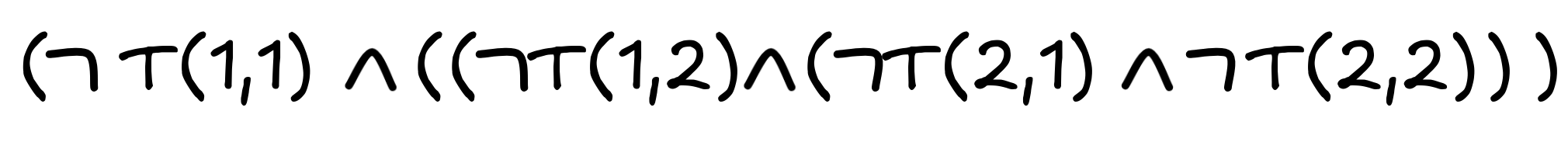

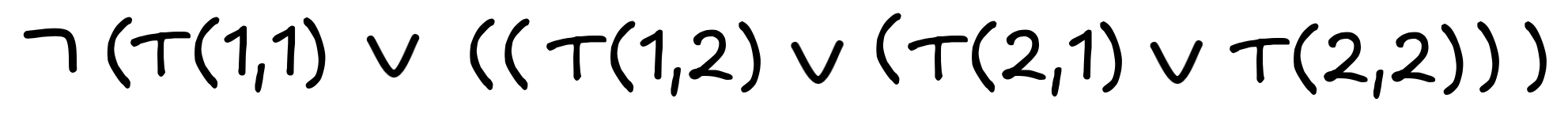

The treasure is nowhere on the disk-world.

-

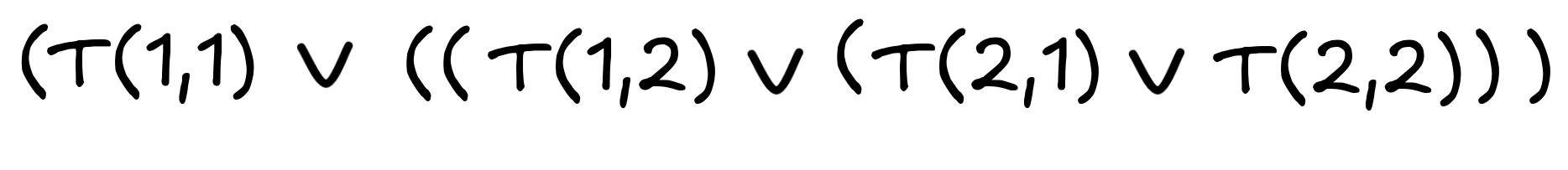

The treasure is somewhere on the disk-world.

-

The treasure is everywhere on the disk-world.

Solution

- A straight-forward representation is

. But an equally valid alternative is:

. But an equally valid alternative is:

.

. - This one is trickier than it might seem at first. I’ve attached a paraphrase to facilitate reading:

- This one has at least two readings in natural language. The most straight-forwardly intended one is

, which reads as if the treasure is not in the lower right and not in the lower left, then it’s in the upper left. But if we take the “only if” parlance seriously, and read the statement as “if the treasure is not in the lower right, then it’s only in the upper left, if it’s not in the lower left,” we get this formula:

, which reads as if the treasure is not in the lower right and not in the lower left, then it’s in the upper left. But if we take the “only if” parlance seriously, and read the statement as “if the treasure is not in the lower right, then it’s only in the upper left, if it’s not in the lower left,” we get this formula:

.

. - This is then just the consequence of the second reading from 3.:

-

- A very straight-forward reading is this:

(“the treasure is not here, not here, not here, and not here”), but an equivalent statement is just the negation of 6.:

(“the treasure is not here, not here, not here, and not here”), but an equivalent statement is just the negation of 6.:

.

. -

-

As you can see, in knowledge representation, we have to handle natural language ambiguity, there are often more than one solution, and things that sound easy in natural language, can be hard to formalize.

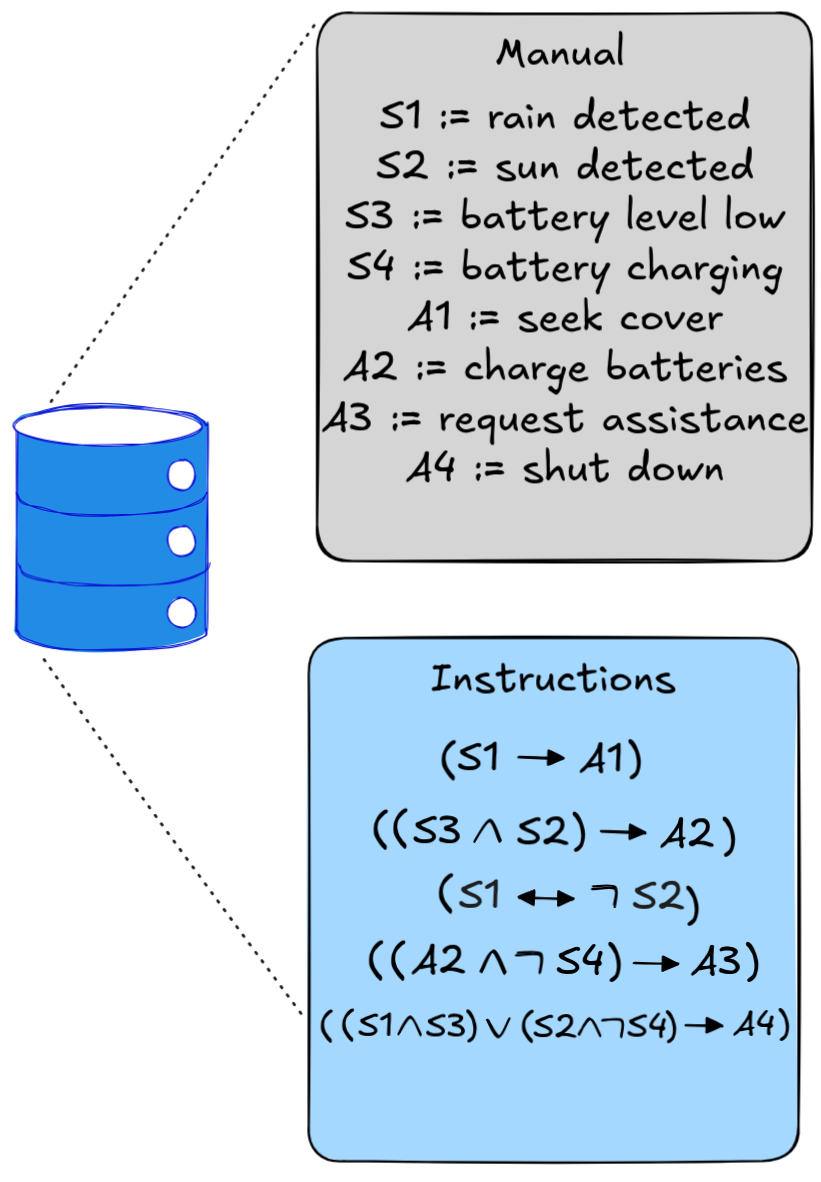

Knowledge extraction

You arrive at an uninhabited planet and find an old space rover that some ancient civilization, which still used expert systems for AI, used to explore the planet.

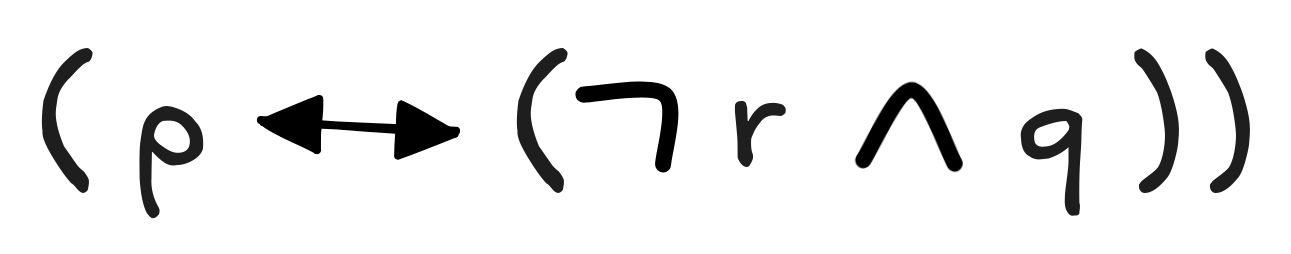

You inspect its KB and find the following:

Explain these instructions in natural language. Can you tell why the robot shut down?

Solution

-

If you detect rain, then seek cover.

-

If your battery level is low and you detect sun, then charge your batteries.

-

You detect rain just in case you don’t detect sun.

-

If you’re charging your batteries and your battery is not charging, then request assistance.

-

If you either detect rain and the battery is low or you detect sun and the battery is not charging, then shut down.

The robot shut down because it’s both sunny and rainy, so what its sensors are telling it is in contradiction to 3., which says that the robot can only ever detect one of the two. Introducing hidden or unexpected contradictions is a grave danger in knowledge representation and great care must be taken to avoid it. This is because in propositional logic, from a contradiction everything follows, which is an issue we’ll discuss more later.

Research

Can the grammar of every formal language be given by a BNF? If so, explain why, if not give a counterexample and explain why it is, indeed, a counterexample.