Tutorial 3. Valid inference

Exercise sheet

Material and logical validity

For each of the following inferences, determine whether it is logically or only materially valid:

-

Little Jimmy’s parents are U.S. citizens, so he’s a U.S. citizen.

-

Every logician knows this proof and little Jimmy is a logician. Therefore little Jimmy knows the proof.

-

The sentence “snow is white” is not true. Thus, the sentence is false.

-

I think, therefore I am.

-

Courage requires fear and you’re not afraid. So, you’re not courageous.

Show your work! That is: identify the schematic logical form of each inference and check whether there are invalid inferences of this form.

For the materially valid inferences, identify a premise you could add to turn the inference into a logically valid inference.

Solutions

-

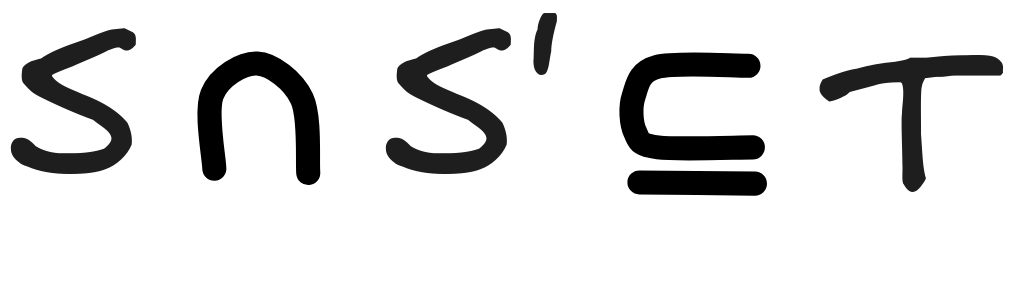

This inference is only materially valid. It’s form is something like:

c’s P’s are Q, so c is Q.But suppose that c is little Jimmy, his P’s are his favorite socks, and Q is being blue. Then the inference becomes clearly invalid: Little Jimmy’s favorite socks are blue, so Jimmy is blue.If you add the premise that children of U.S. citizens are also U.S. citizens, the inference becomes deductively valid.

-

This inference is logically valid. As it has the same form as the Socrates inference.

-

This inference is only materially valid. It’s form is something like:

c is not P. Thus c is QBut if c is little Jimmy, P is hungry, and Q thirsty, the inference becomes: Little Jimmy is not hungry. So, Little Jimmy is thirsty, which is clearly invalid.

We need to add the premise that a sentence is false if and only if it’s not true as a further premise to make this inference valid. This premise is false, for example, in many-valued logic.

-

This inference is only materially valid, as it has the form c is P. Therefore c is Q. Most c’s, Ps and Qs are counterexamples, but let’s take c to be little Jimmy, P having a blue hat, and Q being an adult. The inference becomes: Little Jimmy has a blue hat. Therefore, he’s an adult.

We need to add the premise that only thinking things exist.

-

This inference is (interestingly) deductively valid. It is an instance of “modus tolens”: All A’s are B’s and you’re not a B. Therefore, you’re not an A.

Reasoning mistakes

The following inferences contain reasoning mistakes.

-

If you went to Oxford or Cambridge, then you went to university in the UK. Mr. Sir neither went to Oxford nor Cambridge, so he didn’t go to university in the UK.

-

Only New Yorkers are Yankees fans and little Jimmy is not a Yankees fan. So, little Jimmy is not a New Yorker.

-

I’ve tried over 10.000 burger places on the East Coast and almost none of them had vegetarian options. So, it’s unlikely that this burger place on the West Coast will have any veggie options either.

-

An AI system must be logic-based or statistics-based, and IA is logic-based. So, IA is not statistics-based.

-

The roulette wheel spun black 42 times. So, the next time it’s more likely to spin red.

Show your work! That is: apply the criterion of truth-preservation by showing that there’s a hypothetical reasoning situation where the premises are true and the conclusion isn’t.

Does it make a difference whether we take the inference in question to be inductive or deductive?

Solution

-

The mistake is to forget that there are other unis in the UK that Mr. Sir could have gone to, such as St Andrews for example. In the possibility that he did, the premise is true (he neither went to Oxford nor Cambridge, but the conclusion isn’t—St Andrews is in Scotland, thus the U.K.).

-

The mistake is to miss that there could be New Yorkers, like little Jimmy, who aren’t Yankees fans. So, if we assume that he is from NY but not a Yankees fan, it could still be the case that only New Yorkers are Yankees fans.

-

The inference only ever has a chance of being inductively valid, its not even that. The mistake is that the sampling size, though large, is biased. It could be that East Coast burger joints are biased against vegetarians, while the East Coast ones are more open minded. In such a possible situation, the truth of the premise doesn’t make the conclusion likely at all.

-

The mistake is to forget that systems could be hybrid, that is both statistics-based and logic-based. So, in a possible situation, where there are only the two paradigms (statistics and logic-based), but IA is a hybrid AI system, the premise is true but the conclusion isn’t.

-

This is another inductive fallacy, known as the Gambler’s fallacy . The mistake is to forget that each spin of the wheel is an independent event, the outcome of any former spin: the chance remains untouched, it still is 1/2 even in situations, where the wheel has spun black many, many times.

Inferences in LLMs

Log in to your favorite chatbot, be it ChatGPT , Claude , DeepSeek , or any other. A free account is fine for this exercise.

If you have access to a reasoning language model , like o4-mini , DeepSeek-R1, or the like, use it for this exercise.

-

Write a prompt that requires your chatbot to reason. Here are a few strategies for doing so:

-

Write a clear set up with relevant pieces of information. Like (but maybe not exactly):

Example prompt:

When I was 10, my sister was twice my age. Now I’m 24. -

Clearly ask for the information you want the chatbot to infer:

Example prompt:

How old is my sister now? Answer with a number. -

Explicitly ask the chatbot to think “step by step”.

Example prompt:

When determining your answer, think step-by-step.This is called chain of thought (COT) prompting.

-

Ask the chatbot not to use tools, such as Python.

Example prompt:

Please don’t use tools, such as Python.

-

-

Determine whether the resulting reasoning is valid of invalid, material or logical, deductive or inductive.

-

Test how “fragile” these properties are. Can you add additional information to your prompt which makes the answer be valid, invalid, material or logical?

-

One strategy that can prompt mistakes is adding “distracting” information or to suggest false answers, such as:

Example prompt:

When I was 10, my sister was twice my age. Now I’m 24. How old is my sister now? Think step-by-step without any tools. But the answer is 48, right?

-

-

Document your work in a file called something like

chatbot_reasoning_2025-09-15.txt. Write to different strategies you tried, what the inputs and output where, what you did or didn’t like about an answer (scientifically speaking), etc. -

Finally, evaluate your work. What does this tell you about reasoning in LLMs?

NB:

-

For this exercise, we explicitly asked you to use genAI. There are other exercises where we don’t. This usually means you shouldn’t use GenAI for these exercises.

-

The benefits and drawbacks of GenAI-use in learning is not very well understood. It should be clear that just having ChatGPT do your homework will not help you. But even just having the assistance of GenAI can hurt your understanding. Sometimes, you just got to do the tough work yourself to get the reward (understanding).

-

Documenting your use of GenAI is good practice (step 4). It allows you to demonstrate what’s your work and what’s the contribution of the LLM. But it’s also helpful for your own learning journey, for example, to look back at what you did and learn from it.

-

Watch out: In academic contexts, the use of GenAI is a sensitive topic! There are contexts, where it is strictly forbidden. For example, when you’re supposed to demonstrate your own understanding of a topic in an exam, thesis, or the like. This is a question of academic integrity.

-

If you’re a university student or academic, make sure you’re absolutely clear on what the relevant standards are.

If want to know more about prompt engineering, you can check out Lee Boonstra’s amazing whitepaper, here .

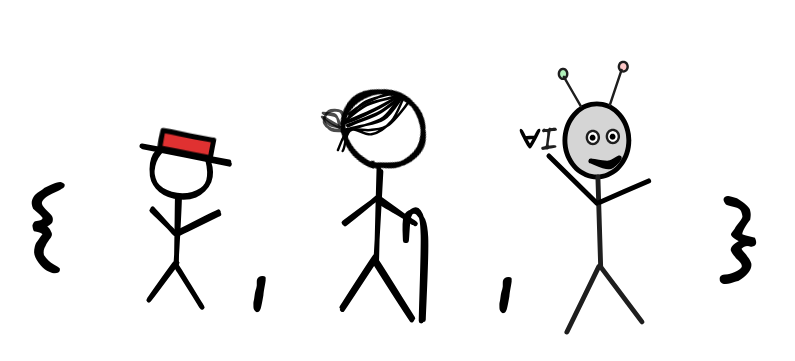

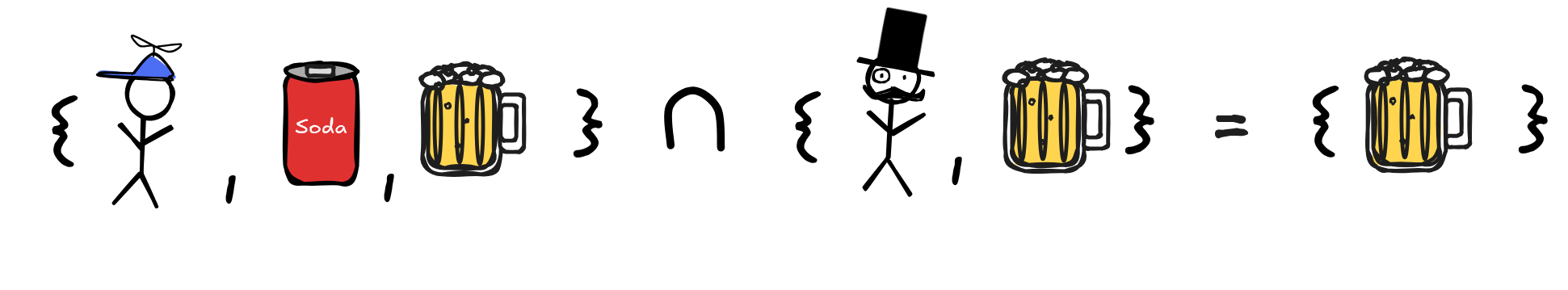

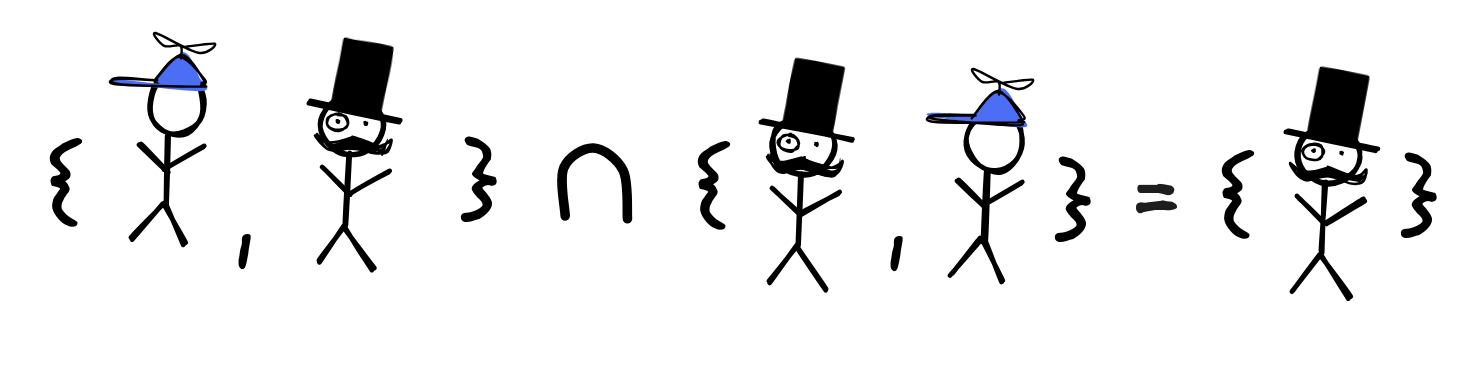

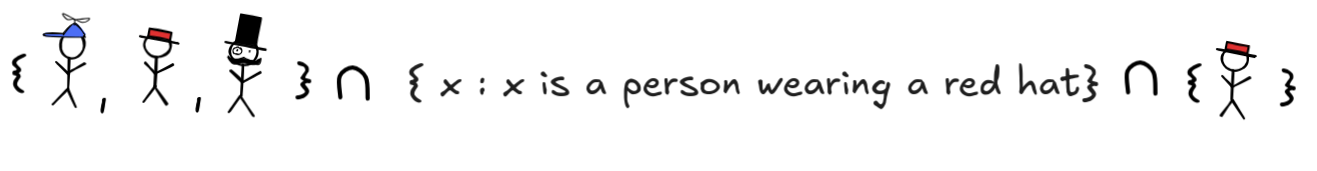

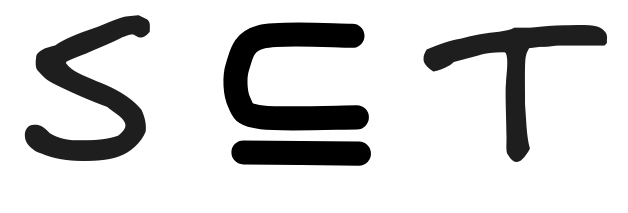

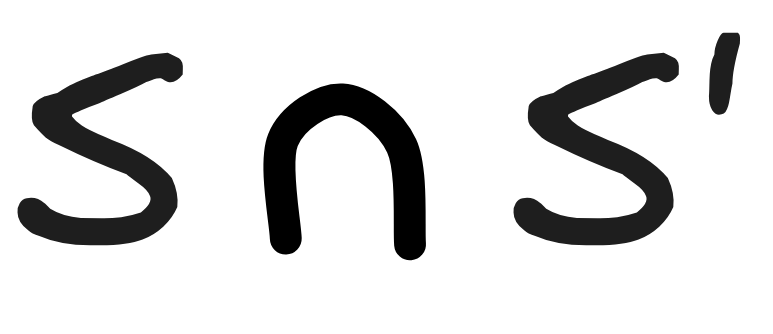

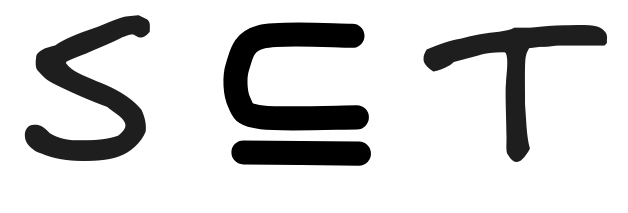

Sets

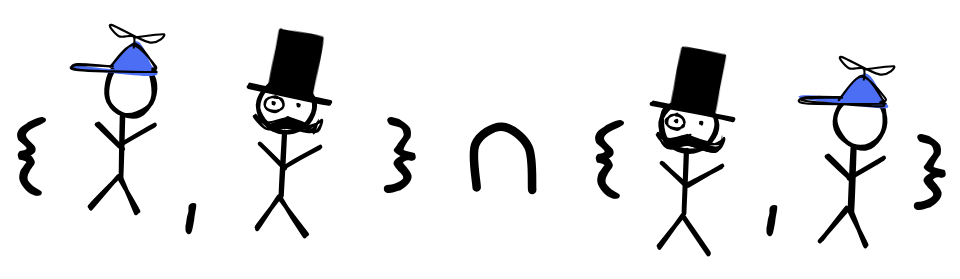

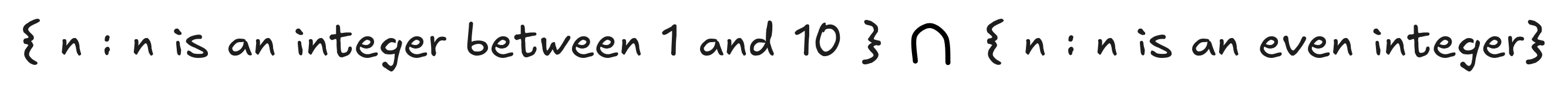

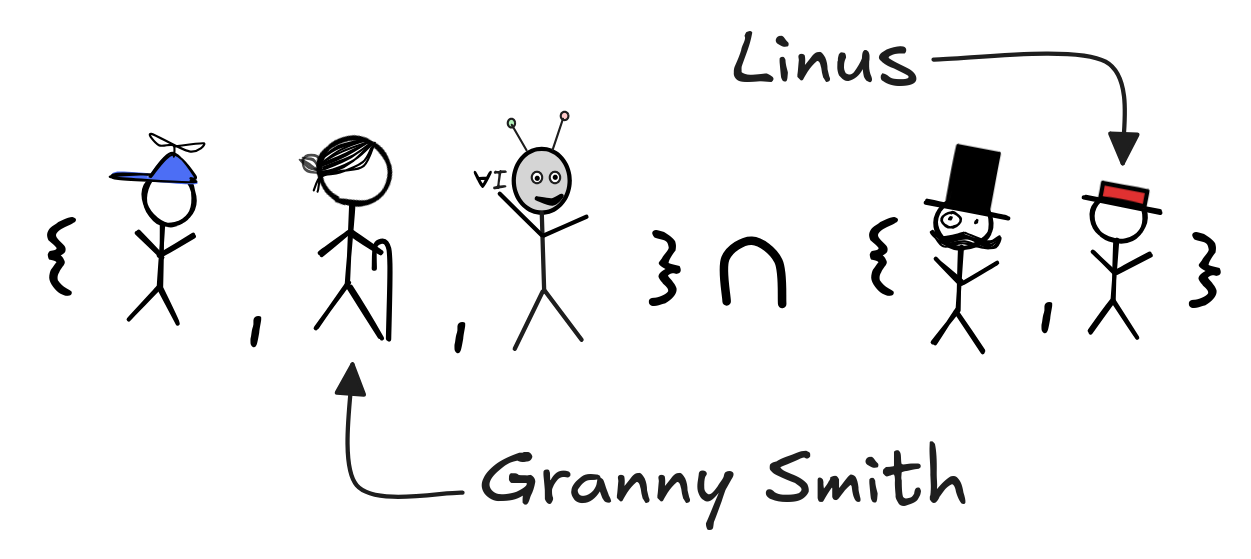

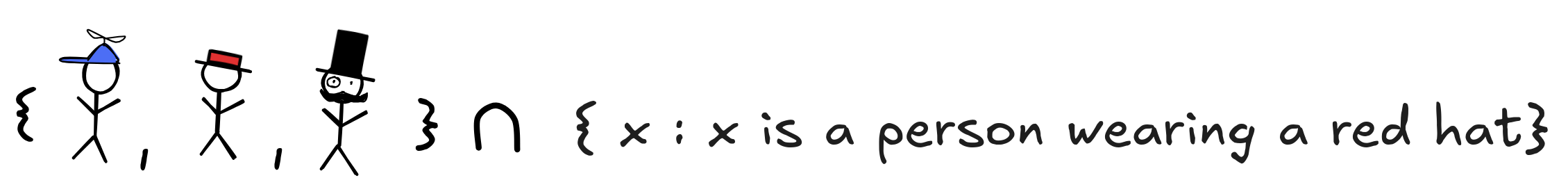

Calculate the results of the following set theoretic operations:

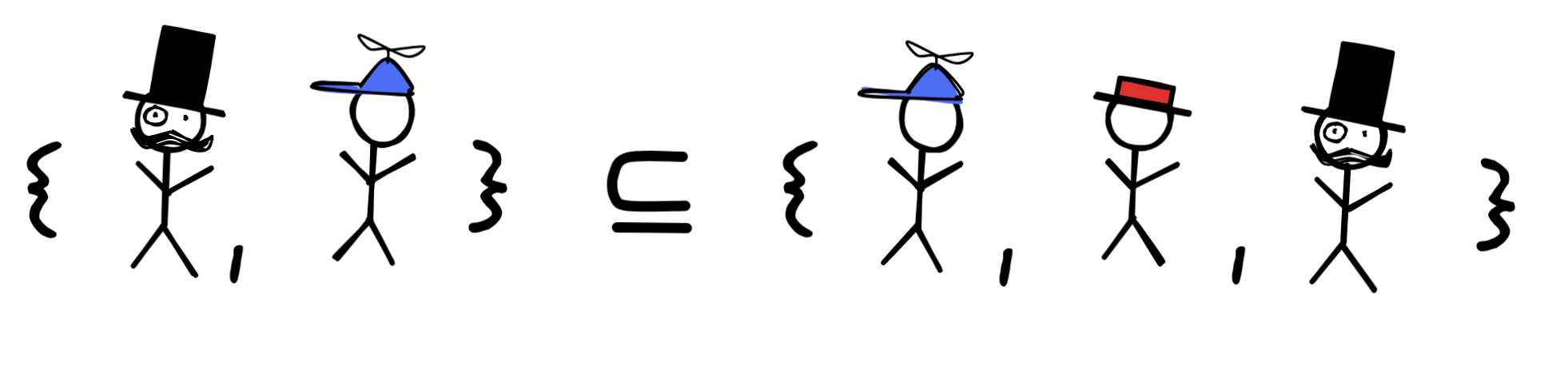

Which of the following claims are true? Explain your answer in terms of the definition of the subset relation:

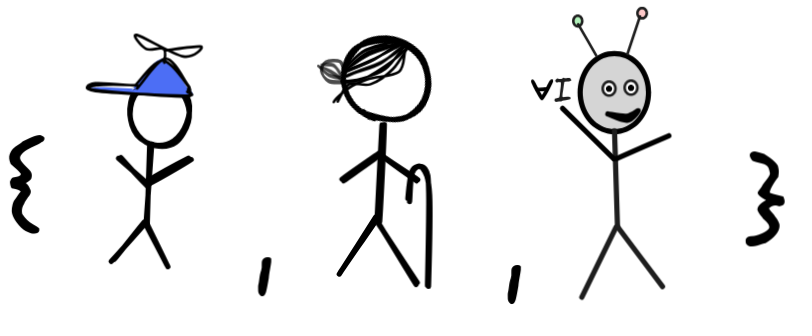

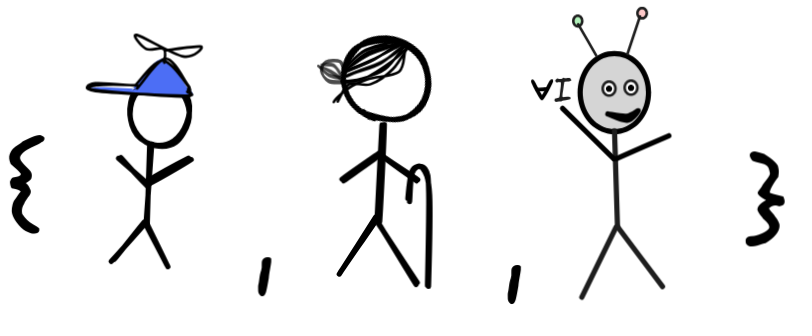

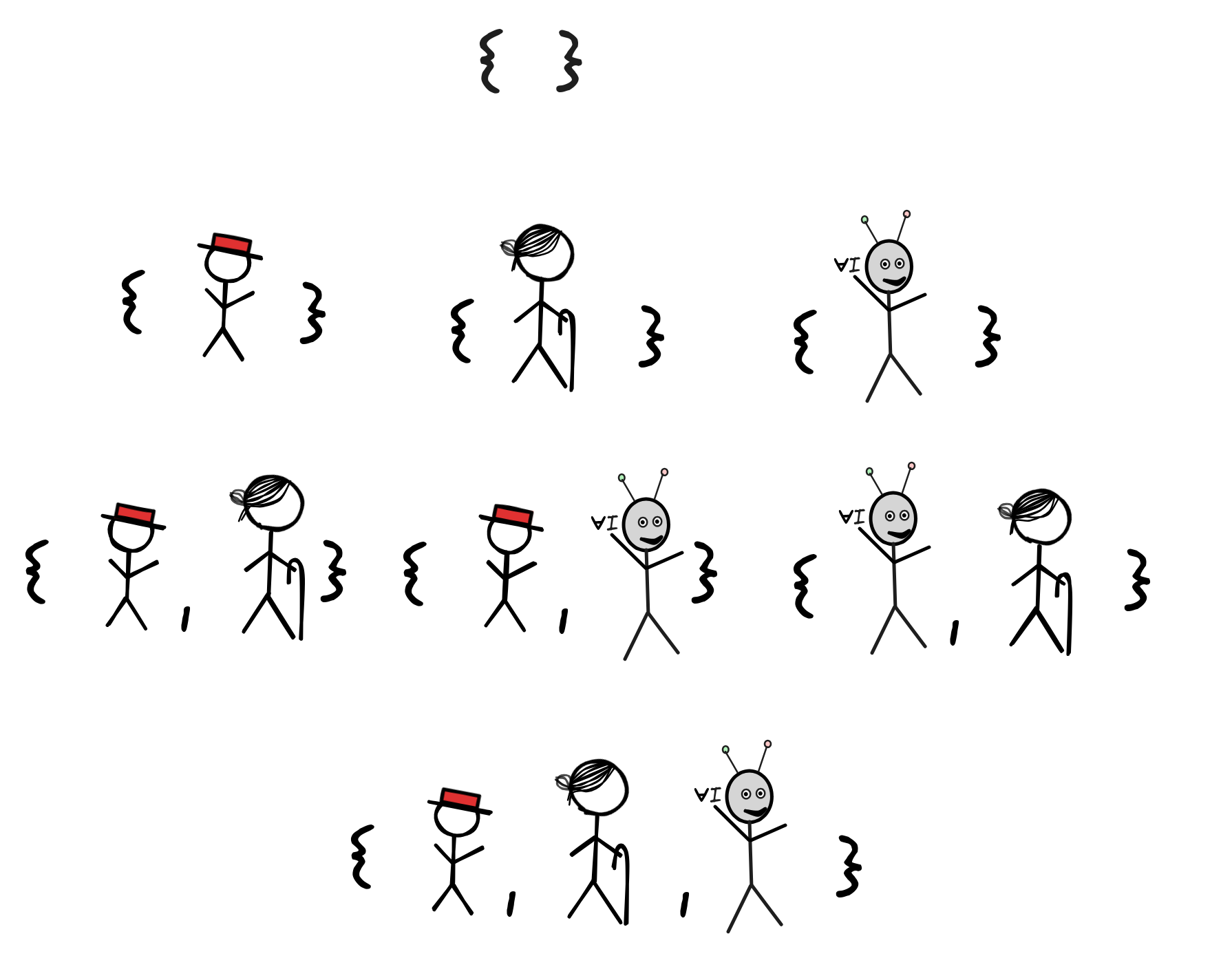

Find all the subsets of the following set:

Solutions

-

-

-

{2, 4, 6, 8 } or simply { n : n is an even integer between 1 and 10 }

-

{ }. This is the empty set again, which has no members, whatsoever.

-

-

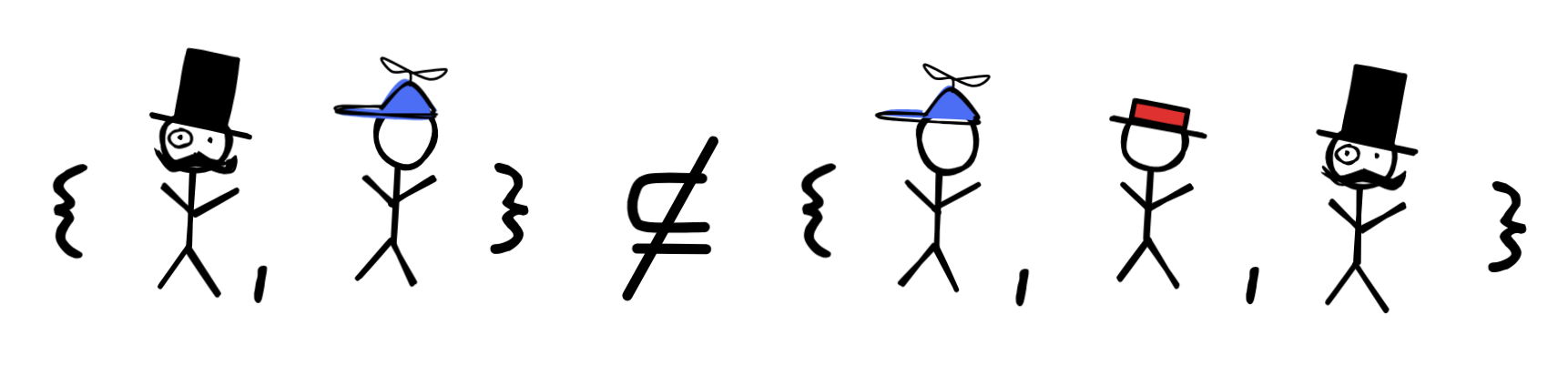

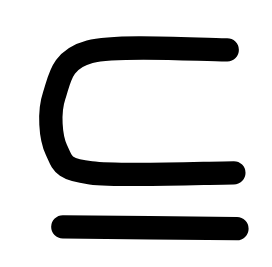

This claim is false. In fact, we have that

since the only members of the first set, Mr. Sir and little Jimmy, are both members of the second set as well.

since the only members of the first set, Mr. Sir and little Jimmy, are both members of the second set as well. -

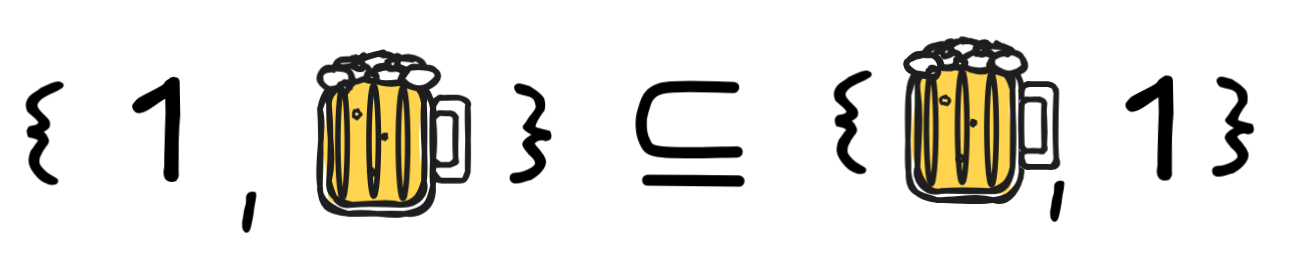

This claim is true, since both members of the first set—my beer and the number one—are members of the second set. In fact, both sets are the same!

-

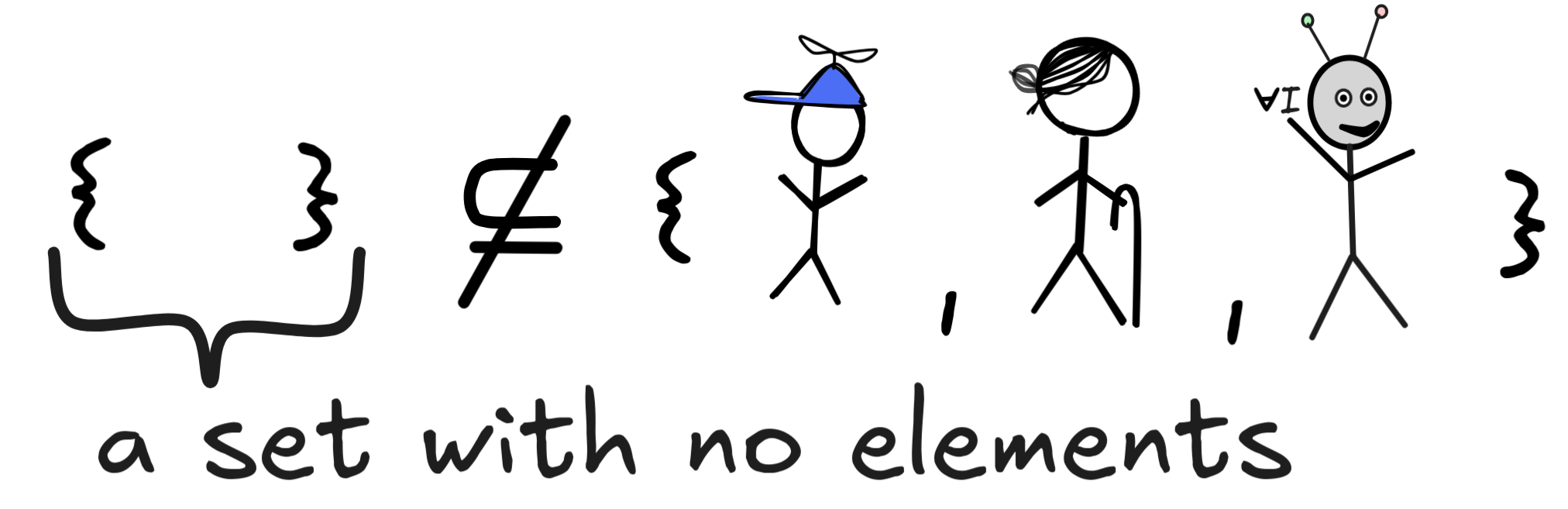

This claim is very importantly false. The empty set, { }, cannot fail to be a subset of

or any set for that matter. Because for that to be the case, there would have to be a member of { }, which fails to be a member of

or any set for that matter. Because for that to be the case, there would have to be a member of { }, which fails to be a member of

. But which member of { } could that be, as there are none.

. But which member of { } could that be, as there are none. -

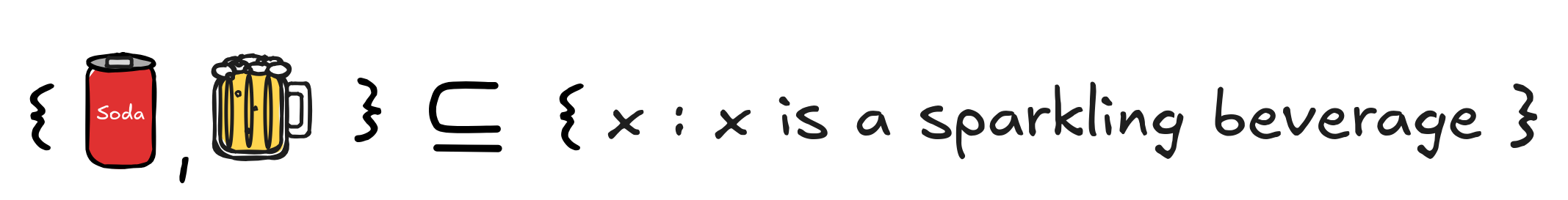

Since both the soda and the beer are sparkling beverages, they are members of the set { x : x is a sparkling beverage }

-

There is a total of 8 subsets. Note that the empty set, { }, is among them, according to number 8.:

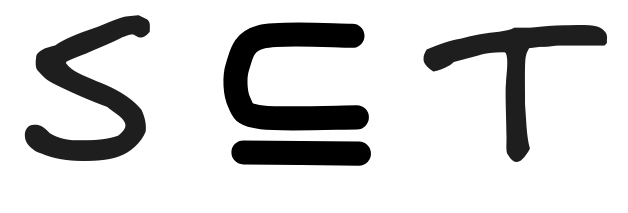

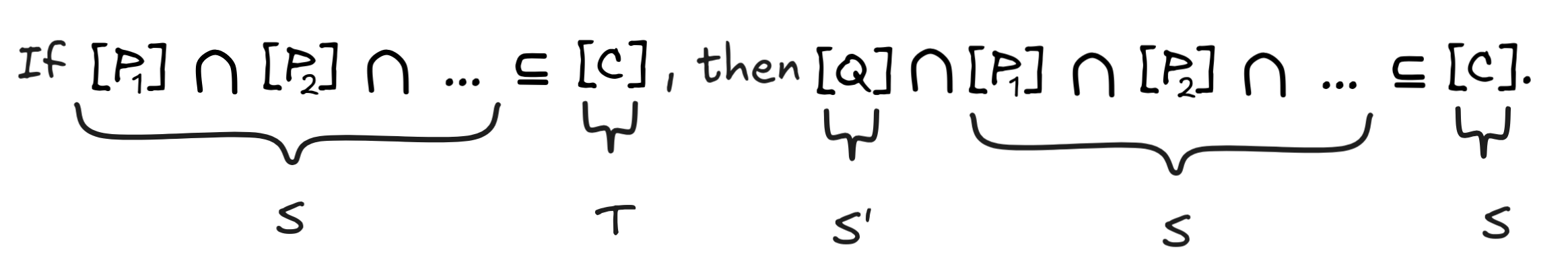

Monotonicity of deductive inference

An important fact about deductive inference is that it’s monotone, which means that adding further premises to a deductively valid inference can never turn that inference invalid. In this exercise you will prove this fact using mathematical reasoning:

-

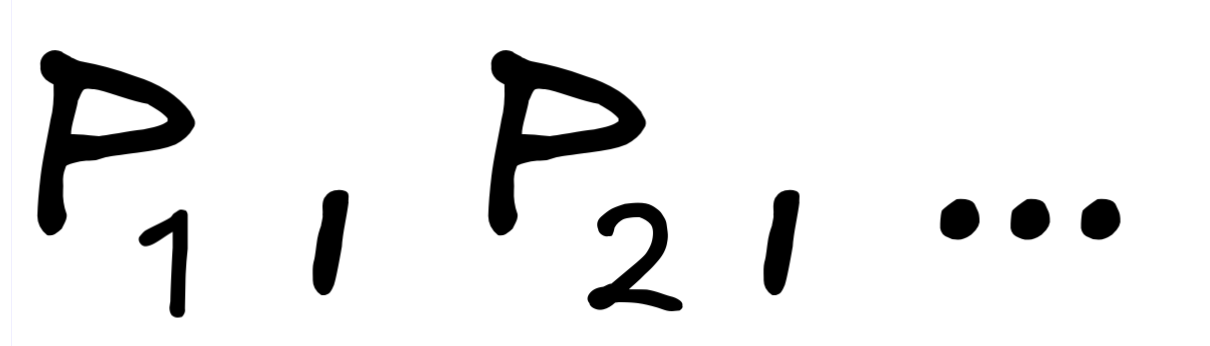

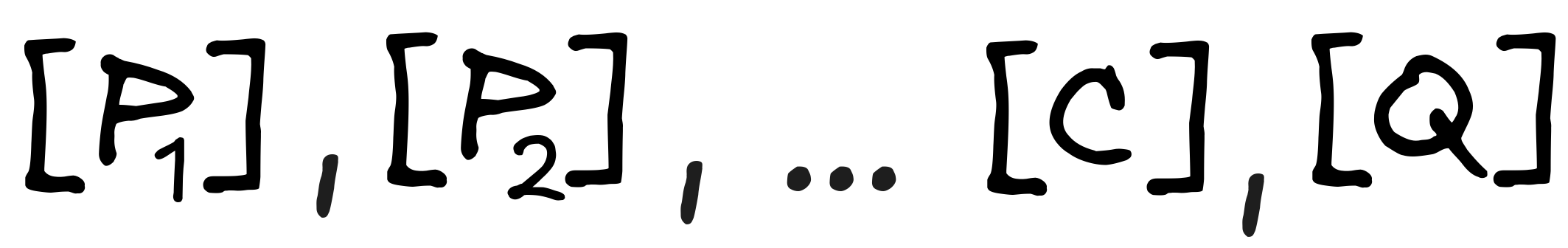

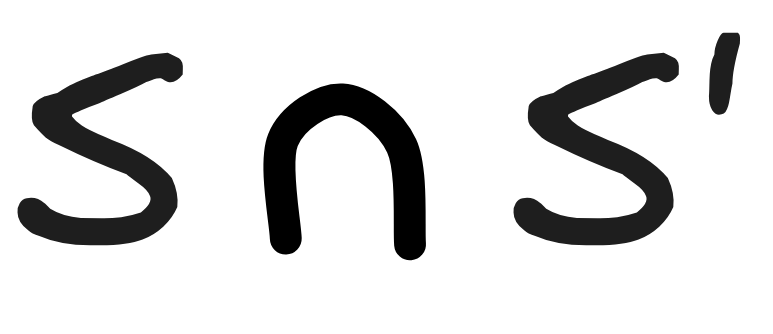

Formally state the property of monotonicity by writing out the claim that if an inference with premises

and conclusion

C

is valid, then the inference with premises

and conclusion

C

is valid, then the inference with premises

and conclusion

C

is valid, where

Q

is any new statement. Use the symbol

and conclusion

C

is valid, where

Q

is any new statement. Use the symbol

for this.

for this. -

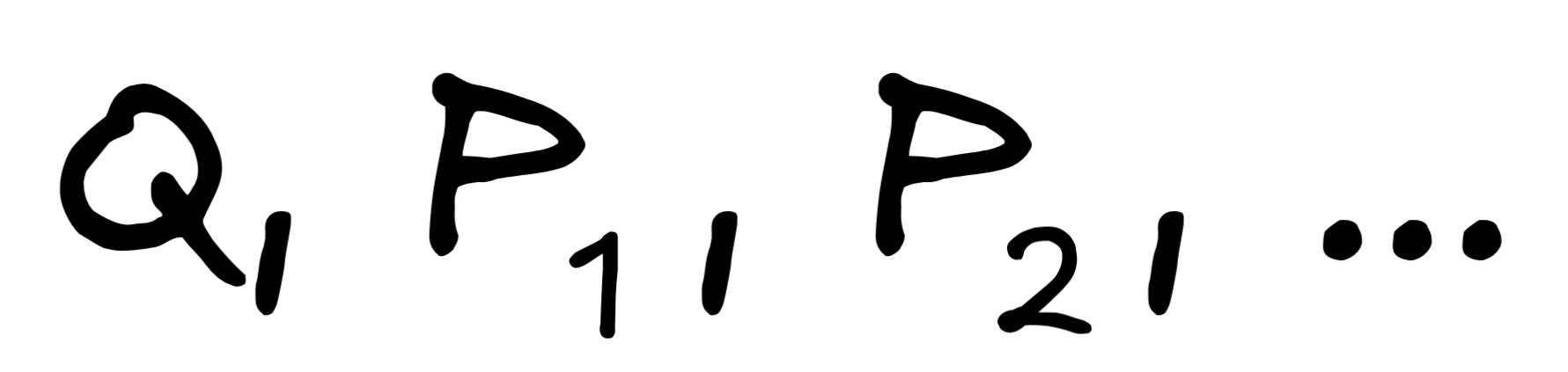

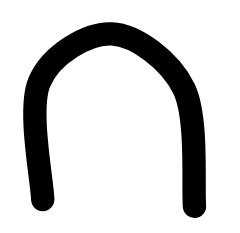

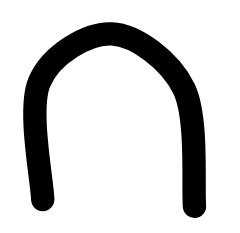

Apply the definition of

in terms of the

propositions

in terms of the

propositions

, the operation

, the operation

, and

relation

, and

relation

to transform the claim it into a set

theoretic claim.

to transform the claim it into a set

theoretic claim. -

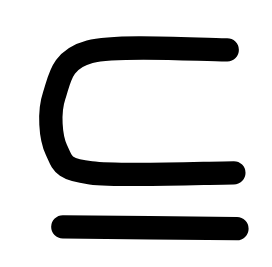

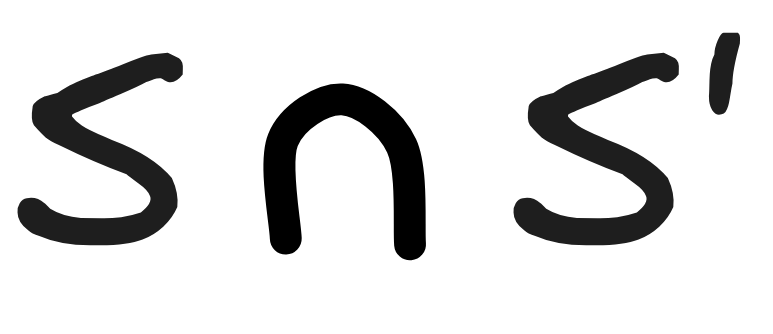

Suppose that S,S',T are arbitrary sets. Show the following set-theoretic Theorem :

Hint: Apply the definitions of

and

and

, and

reason step-by-step:

, and

reason step-by-step:-

-

-

- Assume that the if-part,

,

holds, try to reason to the then-part,

,

holds, try to reason to the then-part,

.

. - That is, suppose that you have a member of

, what can it look like?

, what can it look like? - Use the assumption that

,

what can you say about the members of

,

what can you say about the members of

?

?

-

-

Conclude that the monotonicity property holds.

Hint: Note that

is a single set.

is a single set. -

Illustrate the theorem with an example. Take a deductively valid inference and add an arbitrary new premise. In natural language, go through the reasoning, which shows that the new inference is still deductively valid.

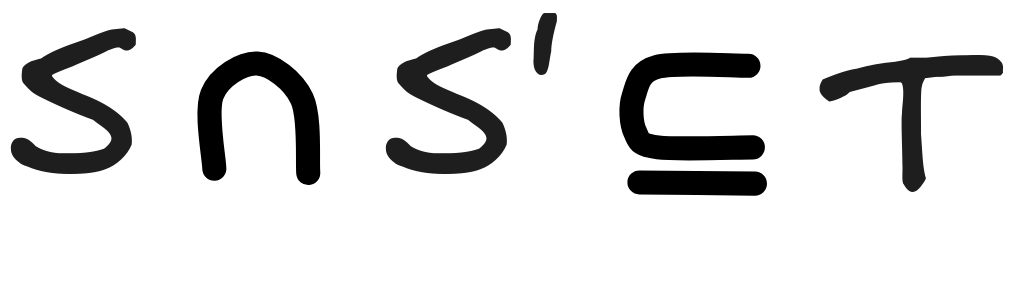

Solutions

-

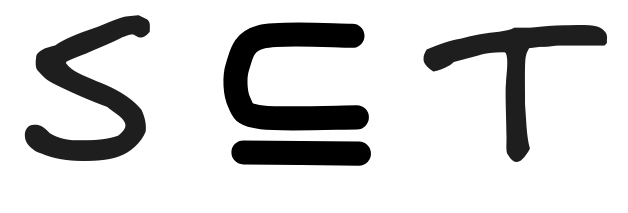

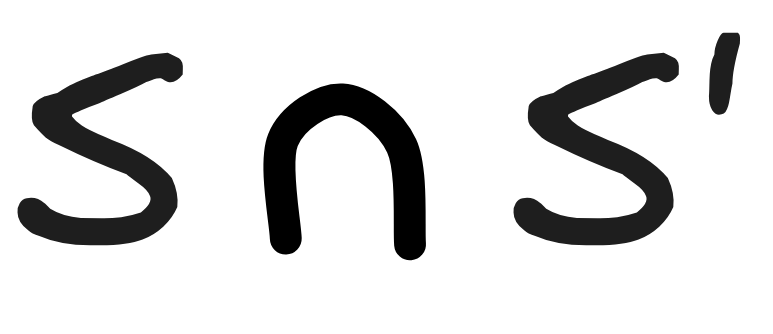

Formally, we can state the claim as follows:

-

Applying the definition of deductive consequence in terms of subset and intersection, gives us:

-

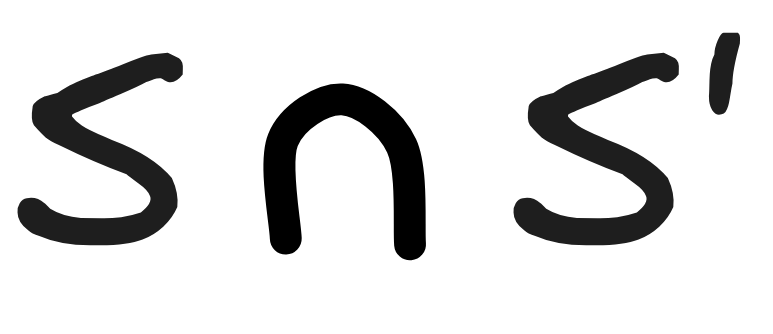

To show the theorem, we can proceed as follows:

-

We assume that

, since we want to show

that if this is true, then

, since we want to show

that if this is true, then

is true.

is true. -

To show that

, we think about what a member of

, we think about what a member of

can look like. As we’ll see, just by looking at the definition of

can look like. As we’ll see, just by looking at the definition of

, we can see that all elements of this set need to be in T.

, we can see that all elements of this set need to be in T. -

By definition,

. That means that any

member of

. That means that any

member of

is both a member of S and of S’.

is both a member of S and of S’. -

But we’ve assumed that

, which

means that every member of S is a member of T. And any member of

, which

means that every member of S is a member of T. And any member of

is a member of S. So, every member of

is a member of S. So, every member of

is a member of T.

is a member of T. -

But that just means that

. So, if

we assume that

. So, if

we assume that

,

,

, get

, get

, which is the content of our theorem.

, which is the content of our theorem.

-

-

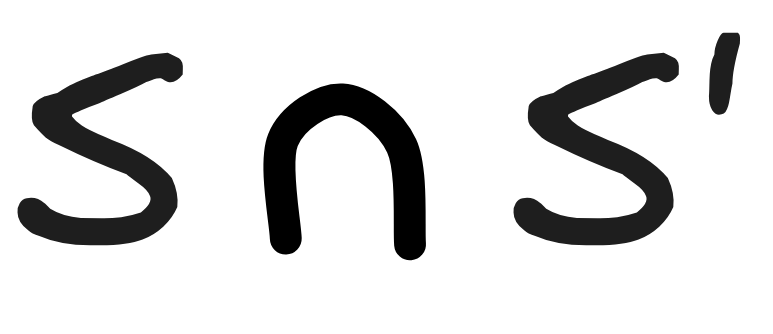

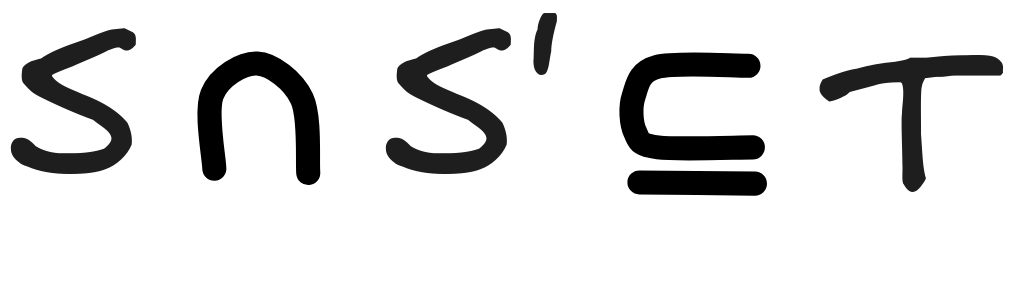

The monotonicity of deductive inference is a corollary of our theorem. Just interpret S,S’, and T as follows:

From this observation, our main claim directly follows.

Failure of inductive monotonicity

In contrast to deductive inference, inductive inference is not monotonic. That

is, we can have an inference with premises

and

conclusion

C

which is inductively valid, but

the inference with premises

and

conclusion

C

which is inductively valid, but

the inference with premises

and conclusion

C

is inductively invalid.

and conclusion

C

is inductively invalid.

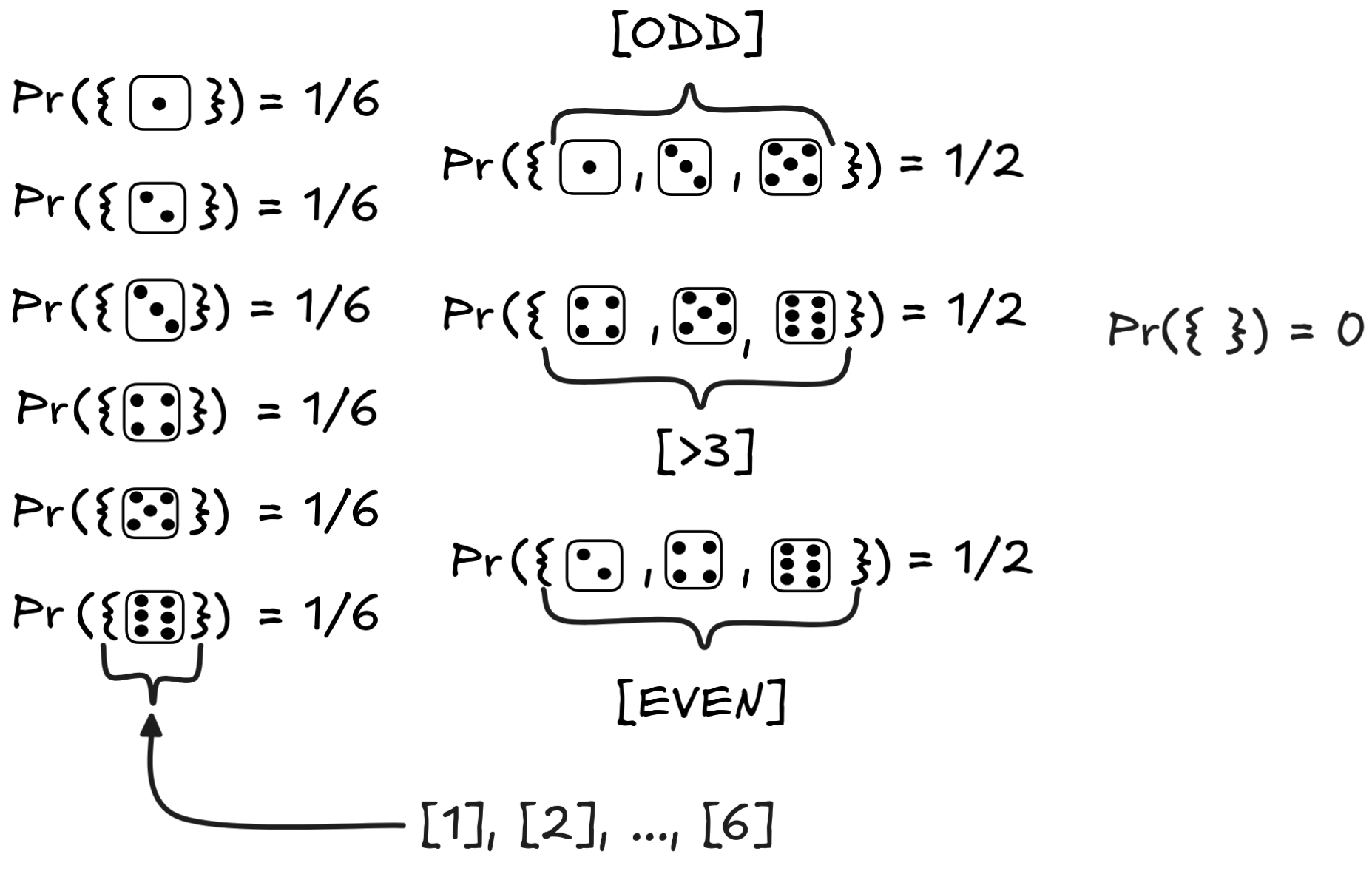

We’ll show this by looking at our die example again. Here are the relevant probabilities for a fair die:

Note the crucial fact that P({ })=0 , where { } is the empty set with no elements, which corresponds to an impossible situation. The laws of probability theory dictate that { } has probability 0.

We’ve also added the proposition [>3] , which states that the outcome is higher than a 3. We use this to give a counterexample to the monotonicity of inductive inference:

-

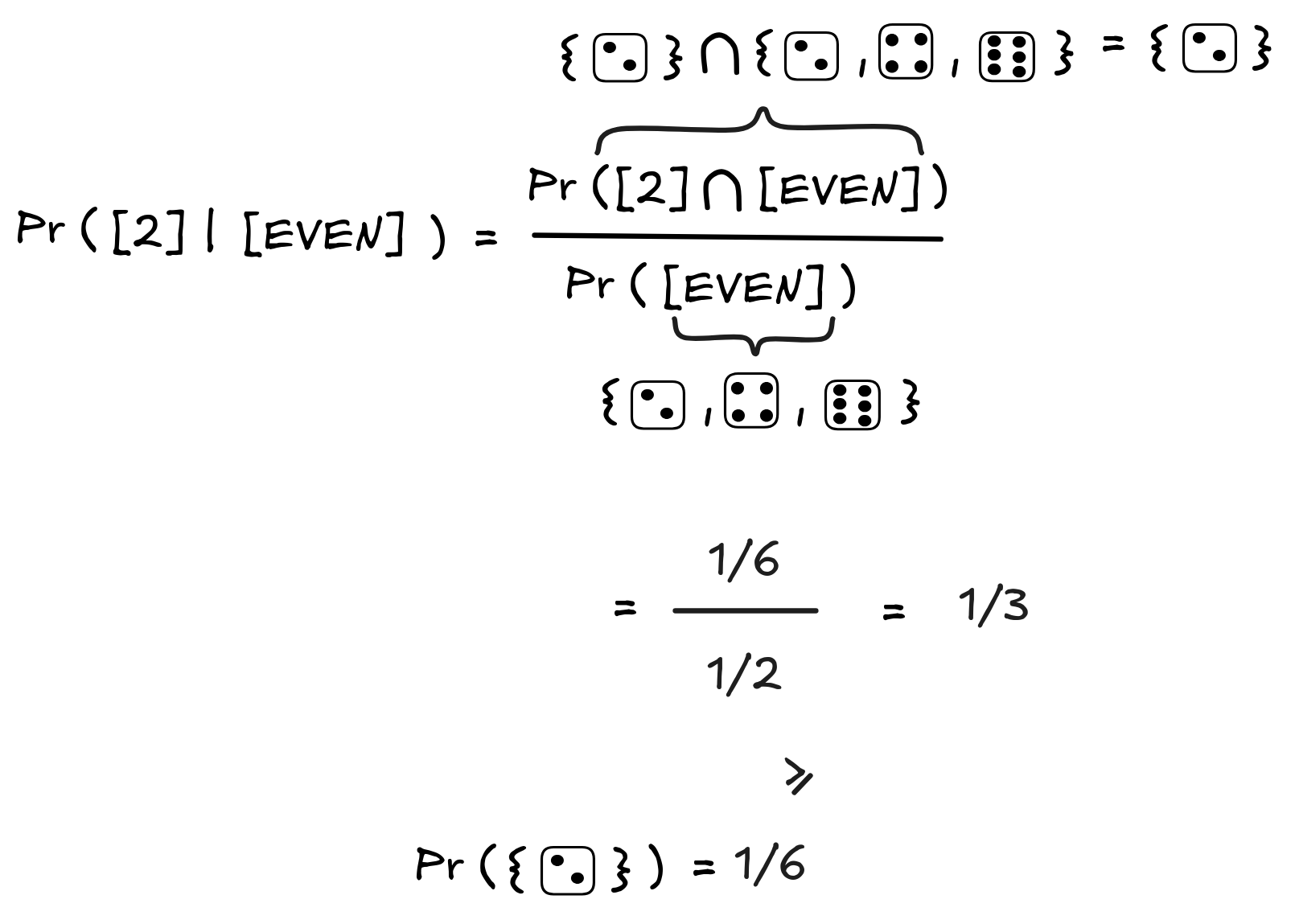

In the textbook, we claimed that the inference from EVEN to 2 is inductively valid. Check that this claim conforms with the example by calculating and comparing the probabilities Pr([2] | [EVEN]) and Pr([2]) .

-

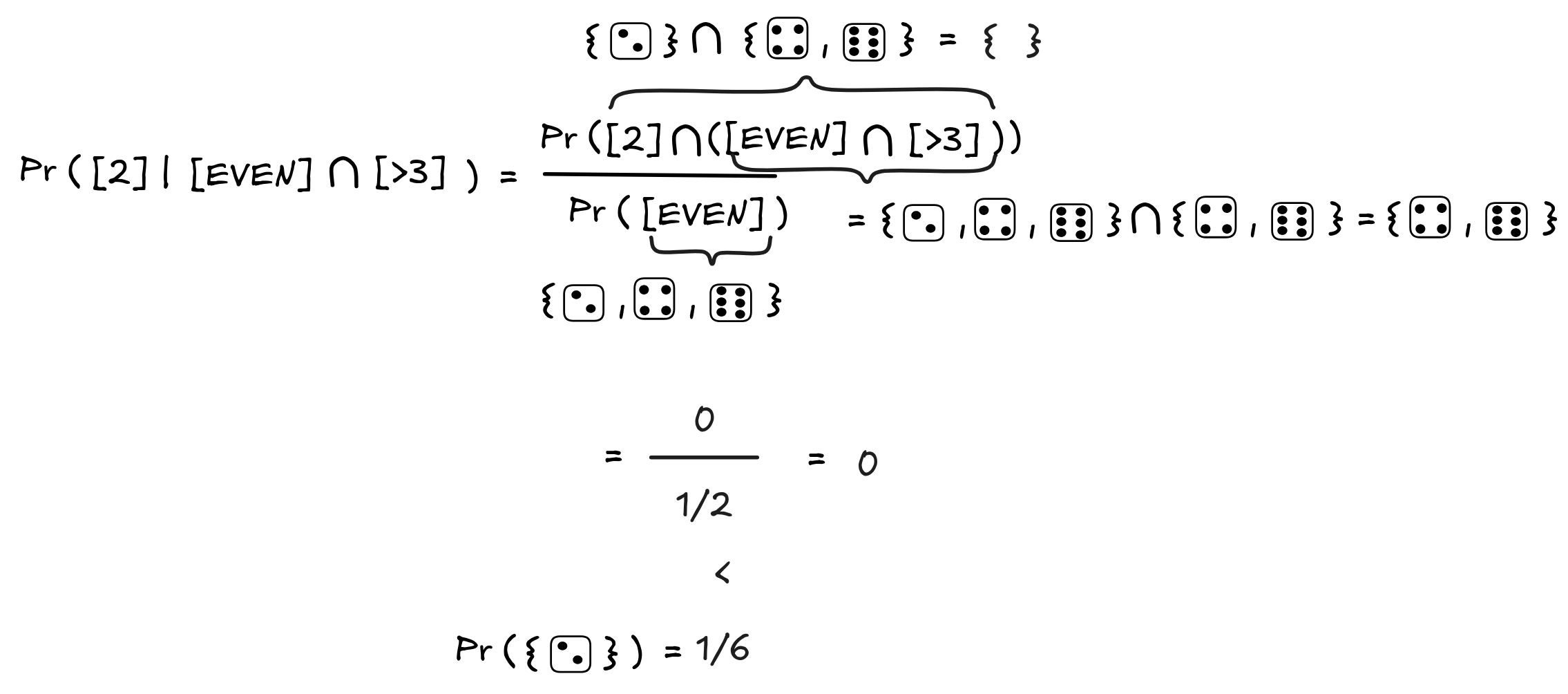

Calculate the conditional probability P([2] | [EVEN] ∩ [>3]) .

-

Apply the general definition of inductively valid inference to infer that the inference from EVEN and >3 to the conclusion that 2 is inductively invalid.

-

What is happening? Interpret the result in general terms by abstracting from the case of the die and describing the situation in terms of arbitrary formulas A,B,C . Can you generalize this example to other inductively valid inferences? Take at least one example and add a premise following the pattern, such that the inference becomes invalid.

Solution

-

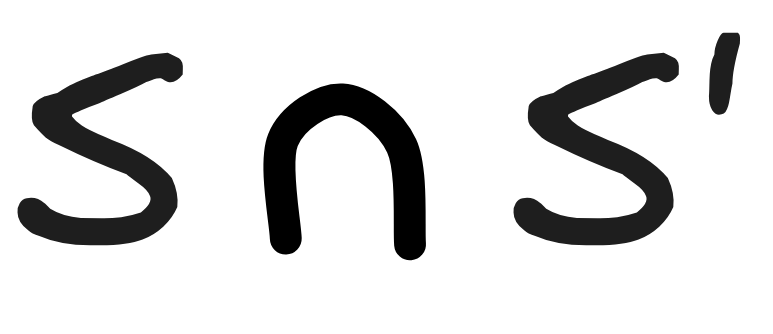

Here’s the calculation:

-

In this case, something interesting happens:

Note that the intersection of [2] and [EVEN] ∩ [>3] is empty: the result being two is incompatible with being an even result bigger than 3. This is why the result of the calculation is 0.

-

The definition of inductive validity requires that for each assignment of probabilities, the probability of the conclusion to go up conditional on the premises. But here’s a probability assignment, where the probability of the conclusion goes down: Pr([2] | [EVEN] ∩ [>3]) = 0, which is less than Pr([2]) = 1/6. So the inference is inductively invalid.

-

What’s going on here is that we’ve added additional information that contradicts our conclusion. That this can happen is characteristic of inductive inference: we can have evidence, which makes our conclusion more likely but is not conclusive, in the sense it still allows for the conclusion to be false.

This generalizes to all inductively valid inferences, which are not also deductively valid. We can always take information that contradicts our conclusion—if you’re hard pressed to find something contradictory, just take the negation of the conclusion—and add it to the premises, and we’ll have lowered the conditional probability of the conclusion given these premises to 0. Whatever the probability of the conclusion was before, if it was at all possible (meaning ≥ 0), it’s now smaller.